The Kindness of Strangers

Not all neighbors are friends. And not all strangers are enemies.

It was October, 1986. I was 25 years old, in my second year of seminary in Dallas, Texas. My fiancée, Brenda, had introduced her brother to a friend she had met in Dallas, and after a brief courtship, they were going to be married in Sandy Creek, New York, 1900 miles away. The bridesmaids' dresses, made by another Dallas friend, were in the back of my car. Our plan was to drive straight through, something I had done solo five months earlier, when I drove up to meet my future in-laws for the first time.

We left early in the morning, and it was a smooth ride all the way to Tennessee. We filled up the tank in Memphis, where a sign on the pump notified us that in the winter months the gasoline contained a high percentage of ethanol. I thought nothing of it until, sometime around 10 p.m., climbing up into the Great Smokies, the car began to shake as the engine lost power. I pulled onto the shoulder, put it in a lower gear, and limped up to the next exit and into the parking lot of a gas station. We were told there that the mechanic would be in around 6 in the morning. We sat, shivering, in the car for about an hour before deciding to see if the engine would still give us trouble. It started smoothly, and we nervously got back on the freeway. All through the night, I kept waiting for the engine to cough and shudder again, but it didn't happen. As the sun rose we found ourselves in Virginia, and stopped for breakfast. Getting back on the highway, I noticed a warning light on the dashboard: something about the battery. It eventually went out.

We drove all day without incident, getting supper at a McDonald's in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, then climbing up into the Pokenoes. It began to rain, not a hard rain, more a high concentration of tiny water droplets that doesn't drum so much as it sizzles. It was probably around 8 p.m. when the shuddering started again, and this time the engine completely stalled. I barely managed to coast to the shoulder. Turning the key in the ignition yielded only a click. Something was broken.

I turned on the flashers, got out a flashlight, and tried waving down cars. There weren't many on this stretch of road, but they were all traveling fast, and not one of them stopped. Rather than that, they flew by, drenching me in their wake. It was cold and windy, and the misty water droplets were hitting me in the face so hard they stung; it was also utterly dark on this stretch of highway. Finally I saw lights approaching that seemed to be slowing down, pulling over onto the shoulder: a semi.

The driver rolled down his window. "Need help?" he called down to me.

"We've had a breakdown," I replied.

"I could take you to the next town," he said. "I know a guy with a tow truck."

"Great!" I jogged back to the car and got Brenda. We climbed up into the cab and we were off.

"Where you headed?" asked the driver.

"Sandy Creek, for a wedding."

"I could take you all the way there. I'm on my way to Watertown."

I thought about it, but didn't like the idea of leaving my car by the side of the road in the middle of Pennsylvania, especially since we'd have to come back for it after the wedding. "That would be wonderful, but the next town should be fine."

"All right, then." He took the exit for Frackville, and let us out at a truck stop, where he waited with us until the tow truck driver arrived. He was a scruffy-looking fellow with an untrimmed beard, gruff, unfriendly, but willing to do whatever we needed to get back on the road. But he wanted payment up front: $75 to either service or tow the car, whichever was required. That happened to be exactly what I had in my wallet. "Do you take plastic?" I asked. "What you got?" "Mobil?" He chuckled. "American Express?" He shook his head. "Visa or MasterCard." I emptied my wallet, and we were off.

Two failed attempts at starting the car by popping the clutch, and it was clear we were going to have to be towed. Back in Frackville, our mechanic looked under the hood and found the culprit: a crack in the alternator. "Good news is, it's easy to replace. Bad news is there's no Toyota dealer in town, so I can't have it ready for you until next Monday."

It was Friday night. The wedding was tomorrow.

We walked to Frackville's tiny downtown, and learned that Greyhound does not take American Express. Brenda used our long distance card to call Sandy Creek, managing to get hold of one of her family members, and to laboriously explain that we were stuck, that there was no way for us to get up there on our own, that someone would have to come and get us, that if they did not the bridesmaids would have nothing to wear at the wedding (all of this apparently eliciting skepticism from whoever she was talking to). Finally she was told that something would be worked out, and someone would come to collect us.

We now had to find a place to spend most of the night, waiting for our ride. Growing up in a Methodist parsonage, my father had always told me that, if ever I was in trouble, I should contact the local Methodist minister. I did that now, calling from a convenience store. He seemed groggy as I spoke to him. I explained our situation--two seminary students on our way to a wedding in northern New York, stranded here by car trouble, just needing a place to stay, even if it was just a pew in the church, until our ride came for us--and he asked, "Why are you calling to me?" "Because we're Methodist seminary students. And we've been learning about Christian charity." There was a long pause; finally he said, "Come on over."

At this point, we had been without sleep for 36 hours. Now we walked across town to the Methodist church and the adjoining parsonage. I knocked on the door. A woman answered. "I've been talking with my husband," she said, "and we're just not comfortable with you sleeping in the church. But here's a voucher for the motel on the other side of town."

I thanked her, and we resumed walking. The rain had, at least, stopped, but the wind that had driven it into my face on the side of the highway was still blowing, and the air had a bite to it. The motel had its "no vacancy" sign turned on, and the office was dark, but I knocked anyway. A young man came to the door. I presented him with the voucher; he pointed at the glowing neon "no." "Please," I begged, "we just need a place to sleep until our ride comes. Could we sleep in the office?" "That's my bedroom," he replied, and shut the door in our faces.

There was one option remaining: the Pine Diner, once again on the far side of the downtown from the motel. We somehow made it over there, sat down in a booth, and ordered hot chocolate, the only item on the menu we could afford with the rest of our cash now in the mechanic's wallet. I got up to use the men's room, where I discovered coin-operated sex toy dispensers: this place catered primarily to truckers. Back in the booth, I found Brenda talking to a waitress, who smiled at me as I slid back into my seat. "You just take all the time you need," she said. "There's no hurry to leave."

We sipped our cocoa, and eventually lay down on the benches of the booth. The next thing I knew, I was being gently shaken awake by Brenda's brother Frank, who had just finished working a swing shift before the rehearsal, and was now going on 24 hours without sleep; and Janet, the pastor who would be performing the wedding later that day. They were the only people in Sandy Creek who could be found to help us. But they would certainly do.

Riding north in the back seat of Janet's car, I saw the sun rise. We would just make it to the wedding. I closed my eyes and fell instantly to sleep.

When there was no room at the inn, or even at the church, it was the diner that came through with a place to sleep. Without the anonymous trucker, we would not have even made it to Frackville. The kindness of strangers had made the difference between life and death that night.

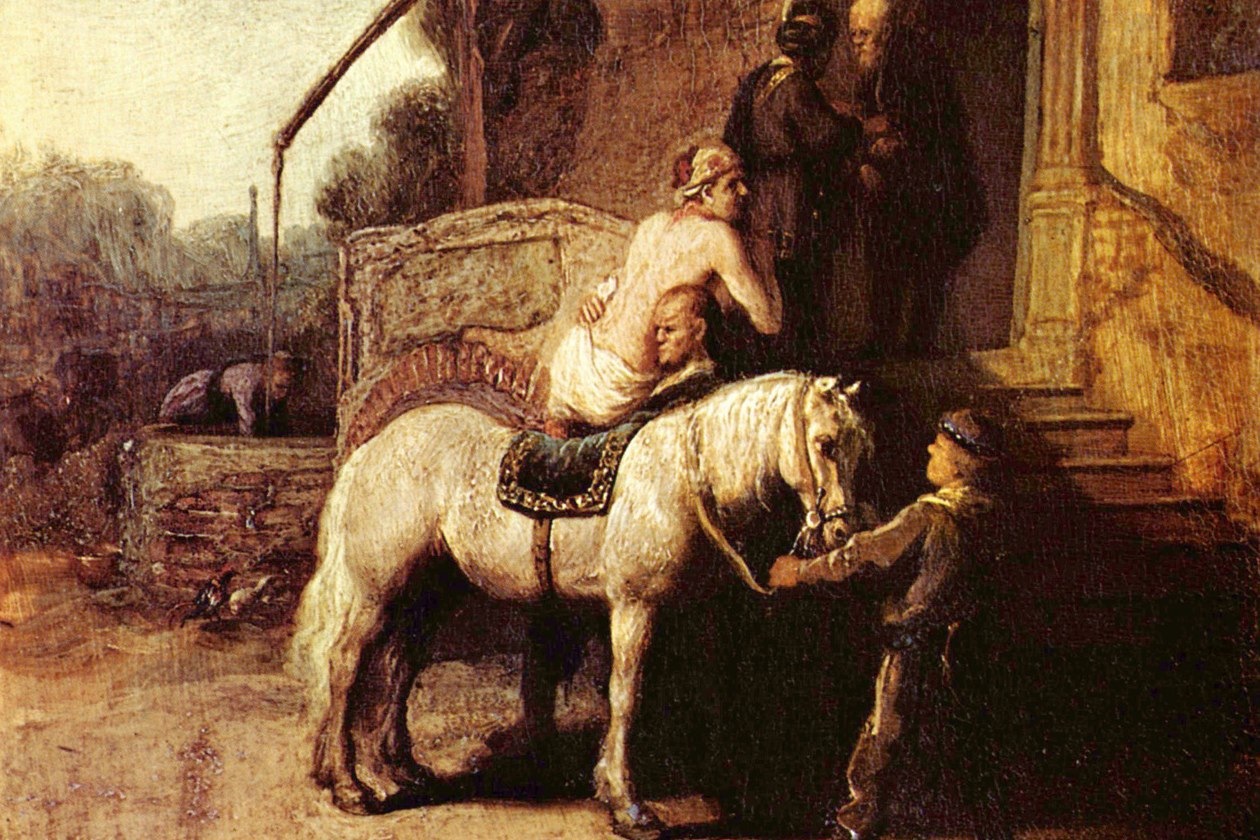

There are two parables in the gospel of Luke that are called the Gospel within the gospel. Yesterday I wrote about the Prodigal. Today's essay stems from the Good Samaritan. This story is not quite as easy to update, as many of its references are rooted in first century Judaism. So pardon me while I do some exegesis:

Jesus is asked by a lawyer who should be considered a neighbor, and thus worthy of acts of mercy. In reply, he tells this story: A man is traveling on foot between Jerusalem and Jericho, the thieves' highway. As happened all too often, he was mugged, stripped of everything he had, and left for dead. Two pious Jews, a priest and a Levite, walked past him and did not stop to help. They may have thought he was dead, and that touching him would render them unclean, but that is beside they point. They do not even stop to find out whether he is breathing. A little later, a Samaritan passes by, and stops, binds his wounds, lifts him up onto his donkey, takes him to an inn, and pays the innkeeper handsomely to tend to him, promising to return on his way home and pay him any other debts that have been incurred. "Who acted like a neighbor?" asks Jesus. "The one who showed mercy." "Go and do likewise."

Thanks to this parable, "Samaritan" is a word that has come to be associated with charity, benevolence, mercy. In fact, Samaritans were despised by first century Jews for reasons I don't wish to elaborate here. Suffice it to say they were heretics and usurpers, relocated to Palestine by an occupying army, granted a large portion of northern Israel from which Jews had been eradicated, and now they had the gall to insist they, too, were of the Chosen people. It stuck in the throat of any patriotic Jew. That a Samaritan would be the one to rescue a Jew, after two pious Jews had refrained from doing so, and thus to fulfill not just the letter, but the heart, of Torah, must have shocked many of the listeners. But this was Jesus' point: it's not who is your neighbor, but who acts like a neighbor, that matters, and sometimes that means reaching across boundaries of intolerance. What's more, when one is lying in a ditch bruised, bloodied, and hypothermic, one can't afford to be picky about where help comes from--especially if one's countrymen are more concerned with keeping the cushions on the pews pristine than helping out a brother in need.

Strangers have often reached out to me in times of need, going many an extra mile in my behalf. They do this without knowing me, without even a sense that it is safe to do so. For all they know, I could be a grifter, out to make a quick buck off a gullible yokel--and that is something that will happen to people who are generous enough that word spreads among members of the homeless community. But that begs the question of the parable: it's not at all about whether the beggar at the door deserves help. It's about how neighborly the person answering the door is willing to be. And clearly, in Jesus' understanding of the Kingdom of God, it's the ones who reach out to help that will inherit the Kingdom. At times, they'll be taken advantage of, but that does nothing to remove the mandate of the Gospel: instead of asking who you're obliged to consider a neighbor, work to be the best neighbor you can be to anyone who needs your help.

I'm here today because of the Samaritans who have entered my life, then promptly left it, usually without even telling me their names. I have not always been as neighborly: I often cross the street to avoid walking by a panhandler, and when they come to my door, or solicit me on the MAX, I tell them "Sorry, no." When I do, I feel a pang of familiarity, imagine myself hearing the doorbell ring, and sending my wife down to hand two weary travelers a worthless motel voucher. The roles are reversed, and I don't like what I see myself doing. Yet still I do it.

How about you? When push comes to shove, will you do the neighborly thing? Or will you cross to the other side of the road, doing your best to ignore the need that is confronting you?

Comments

Post a Comment