My Missionary Position

There's a polite knock on the door. I set aside the project I was working on, walk over to the door, and outside find two neatly dressed young men, nametags on their pockets, black books in their hands, eager to share the Good Word with me. The nametags clearly label them as Mormon missionaries, and I've seen them bicycling around the neighborhood for months, so I'm not surprised by this. They've probably had far lots of doors shut in their faces, many of them rudely, and it must be wearing on them; yet somehow they maintain their good humor and optimism.

Before they can say anything more than "Hello," I tell them this really aren't going to want to talk with us. "Are you sure?" asks one of them, struggling to hide his disappointment. "Have you ever talked to someone about the Mormon faith?"

"Yes, I have," I reply, "and really, this isn't a house you want to spend time on. But good luck." I smile and close the door. I could've gone on, told him that the people in the house are a recently bat-mitzvahed Jewish girl, her secular Jewish mother, and a self-defrocked United Methodist minister, all of us extremely skeptical of their message, and there's no way they would've changed our minds. I could've gone beyond that, shared my theological credentials with him, explained to him that, had the two of them been invited in, they would've found the conversation quickly turning to a historical-critical assault on everything they believe, and that I just don't want to go there. I don't want to take away their innocence and enthusiasm, don't want to turn them away from the good work to which they've devoted a significant portion of their late adolescent lives--work that will enhance in them the quality known as grit, which will in turn make of them better, stronger adults, equipped to serve the world heroically. Instead, I just politely sent them away. No thank you; I really don't want to have this conversation.

This is my approach to missionaries, whether they're Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, or any other faith with an evangelical outreach. I've known colleagues who would invite them in for a snack, a glass of milk, and some dialogue, asking them empathetically about how many doors have been shut in their faces that day, talking about how hard it must be to make cold calls all day long, with very little to show for their efforts. In fact, according to my mother, my father used to do just that, though it must have happened while I was at school, since I don't remember it ever happening when I was home. But that's not what I do. No thank you, I really don't want to have this conversation.

I've had conversations with Mormons before. In 1992, my son Sean spent the first two weeks of his life in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Rogue Valley Hospital. He'd had a birth trauma, something I've written about elsewhere, and it was touch and go for most of the time he was in there. There was a Mormon family in the NICU at the same time with a premature newborn--their fourth, so they knew the drill. They were lovely people. The father had served as a military chaplain, and he seemed open-minded, intelligent, someone I would have enjoyed talking with on a variety of topics. During one of the guardedly optimistic meetings we had with Sean's doctor, she told us she was going to have to have a hard conversation with that couple about not having any more babies. Clearly the mother couldn't carry them to term. I didn't expect that conversation to go over well, as it would be calling into question an article of faith, one of the many I don't discuss when I talk to Mormons.

In 2001, when I went to Utah for my final marathon, I found a homestay in Salt Lake City. I didn't know going on, but it was a Mormon family--though I really shouldn't have been surprised. They were wonderful people, upper middle class, industrious, very open-minded. After the marathon, I was sitting on their back deck, talking with one of them, and he asked if I might want to go to church with them the next morning. I politely declined; I was planning to drop in to a United Methodist service, then hit the road for Bryce Canyon. He seemed disappointed, in the same way those young men at the door were, but he never mentioned it. In fact, he extended another invitation to me, to see one of his daughters perform in a historical pageant when I got back from Bryce. I didn't make any promises--I really was intrigued--but in the end, I just got a motel room for that last night, and flew out early the next morning.

I've had other, less polite experiences with Mormons, primarily when I was in junior high, living in Idaho, and an easy target for bullying. This probably had nothing to do with the bullies' faith, but it colored my attitude toward Mormonism for many years.

In fact, most of the Mormons I've known, whether adults or students, have been generous, polite, friendly people. They genuinely walk the talk. There's no guile about them: they sincerely believe what they're taught, and practice it on a daily basis.

So why don't I want to talk to them? Don't I have even a tiny temptation to buy into their belief system, seeing what lovely, industrious people it turns out?

It comes down to two things: 1) What they believe is nuts. 2) I can't honestly talk about what they believe without telling them the things I know about the Bible, and doing so could endanger their faith--and I don't believe it's my place to do that.

Wait a minute, you're asking. If they're believing doctrines that are crazy, don't I have a responsibility to set them straight?

I used to think it was, in fact, my job to do just that. That's what I came out of my first two years of seminary believing. I took my learning, my dedication to the historical-critical method, my insight into theology and church history, into a rural Illinois congregation, where they listened intently to my sermons and Bible studies, and never questioned what I was saying--at least, not to my face. Emboldened by this, I employed the same tactics in my English church, where they engendered stimulating conversations, and again, it seemed that most people were learning from what I had to offer. Until we talked about Noah's ark, and this man had some problems with it.

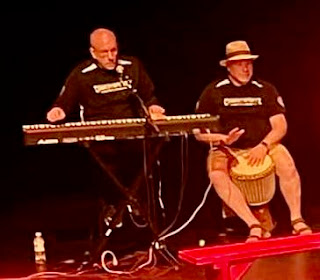

His name was Alan Williams. That's him relaxing during the lunch break from a ramble in Derbyshire with Margaret Chapman. Margaret and Alan were members of Trinity Church. Alan was a Welshman, a stubborn, temperamental man; his wife Joyce was far gentler, less given to explosions. They both attended the Thursday night Bible study I led. One night I was holding forth about the two parallel flood stories in Genesis.

Genesis is cobbled together from multiple sources. At times the final editor tried to harmonize them, create a smooth narrative flow, but for the most part, there's little effort to make them agree with each other. It's as if people knew these dual versions were too different to reconcile, but thought they both offered valuable insights into the nature of God, so they just threw them both in, expecting people to understand this book was more of an anthology than a single, consistent work. In the case of the Creation, there are two clearly distinct stories. One stands on its own; the other is the opening act of a continuous narrative that runs through the flood to slavery in Egypt, the Exodus, the time of the Judges, the founding of Israel as a nation, the Babylonian exile, and finally the return. This epic tale is loosely woven together to present the idea that God is working through history for the salvation of Israel and, through this people, of the whole world. But it's a messy narrative, and the two creation stories are just the beginning of the messiness.

So I was talking about the two flood stories, how they contradicted each other on key points, and suddenly Alan exploded. "If I can't believe this, what can I believe?" he cried, then grabbed his coat and walked out. Joyce followed quickly behind. Soon after that, he stopped attending Trinity.

It took awhile to figure out exactly what had happened, but talking with other members and with Joyce (Alan really didn't want to talk with me), it became clear that Alan had convinced himself that the geological record, along with some ancient legends, proved there had actually been a flood, and this one quasi-historical kernel proved that the Bible and, by extension, Christianity was founded on actual events. His faith was grounded in the story of Noah and his ark, and now I had compromised the foundation of that faith.

After that, I was far more careful about throwing around my ivory tower learning. Faith can be a fragile thing, but it is a vitally important thing to the overall wellbeing of multitudes of people. It is not my place to throw them into crisis just for the satisfaction of proving a point. I genuinely regret the grief I caused Alan, though I don't regret sharing my thoughts about Genesis with him. I just wish I'd been better prepared to deal with what a blow it was to his faith, to gently guide him into a deeper relationship with a God who is more than just a petty miracle worker who'd destroy all life on Earth just to prove a point. But then, I'd have to have a deeper faith myself to do that. I'd have to be something of a missionary. And I'm not.

Seminary can be a faith-crusher. I saw many a sincere candidate reduced to tears by the withering verbal assault of a theology professor. Few professors attended "normal" churches; in fact, many were closet Buddhists, finding that philosophy more compatible with their intellectually rigorous approach to interpreting Scripture and Tradition. Applying those same tools to my own faith--which had never been anywhere near as solid as that of the missionaries at my door--I reduced it, over time, to something so vague and diffuse that it can no longer inform my everyday life. Once one has boiled off all the miracles, contradictions, polemic, and superstition, what's left of Christianity is extremely unsatisfying to a man of my aesthetic and intellectual sensibilities.

But that doesn't make it wrong for others. Nor does my knowledge of the wacky, corrupt roots of Mormonism mean that the faith those boys are sharing, the deep inner connection with God, is as false as the creeds that give it its shape. As Hebrews 11:1 puts it, faith is "the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen." This definition locates faith in feelings rather than beliefs, in a sense of confidence that there is a God who is working for good in the Universe. The specifics of faith are just not important next to its simple presence in one's life. To the extent that I have faith, it's in the goodness of Creation, and in the sense that Creation could not be this good by accident.

I know that this is not enough for many Christians, or for Mormons or anyone else whose faith rests on belief in historical events. Telling a Christian that the multiple versions of a story calls into question its literal historicity, or telling a Mormon that there is absolutely no archaeological record of the presence of proto-Mormons in the Americas, is to challenge the very root of their faith: that these things really happened. It's not my place to do that. If they outgrow it on their own, if they become curious enough to do some study and figure it out themselves, if they are inspired to go to an intellectually rigorous seminary and seriously work with what their professors present to them, then good for them.

As for me, when those fresh-faced boys come to my door, eager to share the Word with me, I will politely turn them away. I don't want to be the one responsible for robbing them of their innocence, destroying their faith, cutting them off from whatever gives their lives meaning.

So no thank you. You really don't want to talk to me. Good luck, and have a lovely day.

Before they can say anything more than "Hello," I tell them this really aren't going to want to talk with us. "Are you sure?" asks one of them, struggling to hide his disappointment. "Have you ever talked to someone about the Mormon faith?"

"Yes, I have," I reply, "and really, this isn't a house you want to spend time on. But good luck." I smile and close the door. I could've gone on, told him that the people in the house are a recently bat-mitzvahed Jewish girl, her secular Jewish mother, and a self-defrocked United Methodist minister, all of us extremely skeptical of their message, and there's no way they would've changed our minds. I could've gone beyond that, shared my theological credentials with him, explained to him that, had the two of them been invited in, they would've found the conversation quickly turning to a historical-critical assault on everything they believe, and that I just don't want to go there. I don't want to take away their innocence and enthusiasm, don't want to turn them away from the good work to which they've devoted a significant portion of their late adolescent lives--work that will enhance in them the quality known as grit, which will in turn make of them better, stronger adults, equipped to serve the world heroically. Instead, I just politely sent them away. No thank you; I really don't want to have this conversation.

This is my approach to missionaries, whether they're Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, or any other faith with an evangelical outreach. I've known colleagues who would invite them in for a snack, a glass of milk, and some dialogue, asking them empathetically about how many doors have been shut in their faces that day, talking about how hard it must be to make cold calls all day long, with very little to show for their efforts. In fact, according to my mother, my father used to do just that, though it must have happened while I was at school, since I don't remember it ever happening when I was home. But that's not what I do. No thank you, I really don't want to have this conversation.

I've had conversations with Mormons before. In 1992, my son Sean spent the first two weeks of his life in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Rogue Valley Hospital. He'd had a birth trauma, something I've written about elsewhere, and it was touch and go for most of the time he was in there. There was a Mormon family in the NICU at the same time with a premature newborn--their fourth, so they knew the drill. They were lovely people. The father had served as a military chaplain, and he seemed open-minded, intelligent, someone I would have enjoyed talking with on a variety of topics. During one of the guardedly optimistic meetings we had with Sean's doctor, she told us she was going to have to have a hard conversation with that couple about not having any more babies. Clearly the mother couldn't carry them to term. I didn't expect that conversation to go over well, as it would be calling into question an article of faith, one of the many I don't discuss when I talk to Mormons.

In 2001, when I went to Utah for my final marathon, I found a homestay in Salt Lake City. I didn't know going on, but it was a Mormon family--though I really shouldn't have been surprised. They were wonderful people, upper middle class, industrious, very open-minded. After the marathon, I was sitting on their back deck, talking with one of them, and he asked if I might want to go to church with them the next morning. I politely declined; I was planning to drop in to a United Methodist service, then hit the road for Bryce Canyon. He seemed disappointed, in the same way those young men at the door were, but he never mentioned it. In fact, he extended another invitation to me, to see one of his daughters perform in a historical pageant when I got back from Bryce. I didn't make any promises--I really was intrigued--but in the end, I just got a motel room for that last night, and flew out early the next morning.

I've had other, less polite experiences with Mormons, primarily when I was in junior high, living in Idaho, and an easy target for bullying. This probably had nothing to do with the bullies' faith, but it colored my attitude toward Mormonism for many years.

In fact, most of the Mormons I've known, whether adults or students, have been generous, polite, friendly people. They genuinely walk the talk. There's no guile about them: they sincerely believe what they're taught, and practice it on a daily basis.

So why don't I want to talk to them? Don't I have even a tiny temptation to buy into their belief system, seeing what lovely, industrious people it turns out?

It comes down to two things: 1) What they believe is nuts. 2) I can't honestly talk about what they believe without telling them the things I know about the Bible, and doing so could endanger their faith--and I don't believe it's my place to do that.

Wait a minute, you're asking. If they're believing doctrines that are crazy, don't I have a responsibility to set them straight?

I used to think it was, in fact, my job to do just that. That's what I came out of my first two years of seminary believing. I took my learning, my dedication to the historical-critical method, my insight into theology and church history, into a rural Illinois congregation, where they listened intently to my sermons and Bible studies, and never questioned what I was saying--at least, not to my face. Emboldened by this, I employed the same tactics in my English church, where they engendered stimulating conversations, and again, it seemed that most people were learning from what I had to offer. Until we talked about Noah's ark, and this man had some problems with it.

His name was Alan Williams. That's him relaxing during the lunch break from a ramble in Derbyshire with Margaret Chapman. Margaret and Alan were members of Trinity Church. Alan was a Welshman, a stubborn, temperamental man; his wife Joyce was far gentler, less given to explosions. They both attended the Thursday night Bible study I led. One night I was holding forth about the two parallel flood stories in Genesis.

Genesis is cobbled together from multiple sources. At times the final editor tried to harmonize them, create a smooth narrative flow, but for the most part, there's little effort to make them agree with each other. It's as if people knew these dual versions were too different to reconcile, but thought they both offered valuable insights into the nature of God, so they just threw them both in, expecting people to understand this book was more of an anthology than a single, consistent work. In the case of the Creation, there are two clearly distinct stories. One stands on its own; the other is the opening act of a continuous narrative that runs through the flood to slavery in Egypt, the Exodus, the time of the Judges, the founding of Israel as a nation, the Babylonian exile, and finally the return. This epic tale is loosely woven together to present the idea that God is working through history for the salvation of Israel and, through this people, of the whole world. But it's a messy narrative, and the two creation stories are just the beginning of the messiness.

So I was talking about the two flood stories, how they contradicted each other on key points, and suddenly Alan exploded. "If I can't believe this, what can I believe?" he cried, then grabbed his coat and walked out. Joyce followed quickly behind. Soon after that, he stopped attending Trinity.

It took awhile to figure out exactly what had happened, but talking with other members and with Joyce (Alan really didn't want to talk with me), it became clear that Alan had convinced himself that the geological record, along with some ancient legends, proved there had actually been a flood, and this one quasi-historical kernel proved that the Bible and, by extension, Christianity was founded on actual events. His faith was grounded in the story of Noah and his ark, and now I had compromised the foundation of that faith.

After that, I was far more careful about throwing around my ivory tower learning. Faith can be a fragile thing, but it is a vitally important thing to the overall wellbeing of multitudes of people. It is not my place to throw them into crisis just for the satisfaction of proving a point. I genuinely regret the grief I caused Alan, though I don't regret sharing my thoughts about Genesis with him. I just wish I'd been better prepared to deal with what a blow it was to his faith, to gently guide him into a deeper relationship with a God who is more than just a petty miracle worker who'd destroy all life on Earth just to prove a point. But then, I'd have to have a deeper faith myself to do that. I'd have to be something of a missionary. And I'm not.

Seminary can be a faith-crusher. I saw many a sincere candidate reduced to tears by the withering verbal assault of a theology professor. Few professors attended "normal" churches; in fact, many were closet Buddhists, finding that philosophy more compatible with their intellectually rigorous approach to interpreting Scripture and Tradition. Applying those same tools to my own faith--which had never been anywhere near as solid as that of the missionaries at my door--I reduced it, over time, to something so vague and diffuse that it can no longer inform my everyday life. Once one has boiled off all the miracles, contradictions, polemic, and superstition, what's left of Christianity is extremely unsatisfying to a man of my aesthetic and intellectual sensibilities.

But that doesn't make it wrong for others. Nor does my knowledge of the wacky, corrupt roots of Mormonism mean that the faith those boys are sharing, the deep inner connection with God, is as false as the creeds that give it its shape. As Hebrews 11:1 puts it, faith is "the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen." This definition locates faith in feelings rather than beliefs, in a sense of confidence that there is a God who is working for good in the Universe. The specifics of faith are just not important next to its simple presence in one's life. To the extent that I have faith, it's in the goodness of Creation, and in the sense that Creation could not be this good by accident.

I know that this is not enough for many Christians, or for Mormons or anyone else whose faith rests on belief in historical events. Telling a Christian that the multiple versions of a story calls into question its literal historicity, or telling a Mormon that there is absolutely no archaeological record of the presence of proto-Mormons in the Americas, is to challenge the very root of their faith: that these things really happened. It's not my place to do that. If they outgrow it on their own, if they become curious enough to do some study and figure it out themselves, if they are inspired to go to an intellectually rigorous seminary and seriously work with what their professors present to them, then good for them.

As for me, when those fresh-faced boys come to my door, eager to share the Word with me, I will politely turn them away. I don't want to be the one responsible for robbing them of their innocence, destroying their faith, cutting them off from whatever gives their lives meaning.

So no thank you. You really don't want to talk to me. Good luck, and have a lovely day.

Comments

Post a Comment