Personality

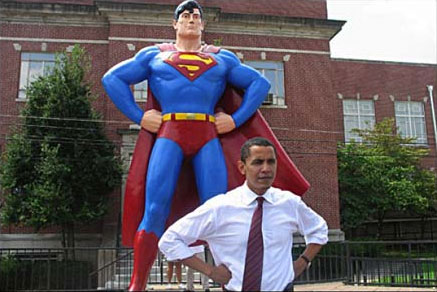

There's a lot of irony to this picture, and especially to where I found it: an anti-Obama blog accusing him of heading a cult of personality.

There are at least two problems with that notion: first, apart from his speeches, Barack Obama has demonstrated in the first four and a half years of his presidency that he is, if anything, less charismatic than his predecessor. Second, Superman is, of all superheroes, the one demonstrating the least personality charisma. Try having a conversation with him, and you discover in no time at all that, like Obama, he's very impressive in what he does with the powers he has, but schmoozing is not one of them.

For a person to be the center of a cult of personality, he or she must, in fact, have a personality. Powerful speeches or a rocking physique do not generate a cult. Having a personal touch, making people feel like you're addressing them individually, that you really do feel their pain and care deeply about alleviating it, and doing so on a massive scale--that's what it takes to generate a cult. Watch the first few minutes of Primary Colors, as John Travolta channels Bill Clinton, and you get it. He turns on the magic, and everyone in the room believes this candidate is his or her personal friend. I've known people who could do that, even been caught up in the powerful gravitational field they exert. Only long after the experience did I realize that I mattered no more to them than any other ordinary person in the room.

Charisma can be a dangerous thing. Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Mao, Castro, Kim, Chavez, Amin--all have more-or-less used their charisma to create authoriatrian, if not totalitarian, regimes. It transcends ideologies, encompassing both fascists and socialists. Having the power, it is all too tempting to use that power, to equate charisma with merit and, moving on from there, decide one knows better than anyone else what a nation needs. It's far too easy to both consolidate power and overestimate one's wisdom when one is surrounded by fawning fans.

Of course, not all personality cults function on a global scale. Most that I've known have existed in either classrooms or sanctuaries.

I came under the sway of two when I was in high school, a developmental stage particularly susceptible to idolization of charismatic leaders. One was a band director, the other a pastor.

Dan Ogren became the band director at Philomath High School in September, 1977. It was, I think, his first teaching job. He was young, energetic, enthusiastic, and gifted. I was a junior, and had for two years learned under the direction of a competent but unexciting educator who lost his position following allegations of an inappropriate relationship with a student (he was ultimately acquitted, but too late to save his career). Mr. Ogren was especially keen on jazz. I'd started playing in the jazz ensemble a year earlier, but had no sense yet of how to swing. I learned it from Mr. Ogren. I learned many things from him, and by the time I graduated, I had decided what I wanted to be based almost exclusively on his example: a band director.

As I've written elsewhere, I did not have a vast store of musical talent. I had some keyboard skills, and knew things about music theory that were unusual for someone my age, but most of that came from piano lessons with my mother. On the trumpet, which was by now my major instrument, I was unexceptional. If you had interviewed my teachers--including Mr. Ogren, I suspect--they would most likely have agreed that I should pursue a career in the humanities or journalism.

I enjoyed those disciplines, even seemed to have some talent in them, especially in writing; but none of those teachers seemed like anyone I wanted to be. I wanted to be Dan Ogren.

In retrospect, I realize a lot of what made me gravitate to him was his personality. He wasn't just dedicated; I've had dedicated teachers, and learned a great deal from them, without ever becoming a fanboy. Daniel Ogren had a special knack for communicating with young people and making them feel confident and valued. He still has it, by the way; since returning to teaching eleven years ago, I've bumped into him a few times, and had the privilege of seeing him work with junior high bands, including my own. He gets, and keeps, their attention, and they want to learn from him.

The pastor I mentioned earlier was Bill Walker. I met him at a church camp, at which he was our "theologian in residence"--chaplain for the week. Every morning during devotions, he brought us a message that seemed directed to our very hearts. It was casual, personal preaching, and it made me want very much to spend us much time as I could with this man. He was the same way one-on-one; spend any time with him, and you felt instantly that he was genuinely interested in and concerned for you.

Over the next fifteen years, I had many occasions to meet again with Bill Walker: another camp, ordination interviews, annual conference. Once I began preaching, I modeled my delivery on my memory of him. Then, one day in 1992, he broke my heart.

Bill Walker, it turns out, was either a closeted gay man or bisexual, and for decades had been living a double life, engaging in risky anonymous sexual encounters, contracting AIDS, and giving it to his wife. When she died, it was attributed to cancer. When he died a few years later, it was also called cancer--until one Sunday morning, soon after his death, when a man walked into the last church Bill Walker served and began loudly demanding an audience, saying the man so many had idolized, the model for so many young ministers, had molested him when he was a teenager. Once the story came out, many more came forward, until it was clear Bill Walker had not restricted his double life to casual partners outside the church, but had, in fact, had a pattern of grooming and molesting teenaged boys.

The Bishop called a special session of the clergy to share this information, wanting us to be aware of it before it hit the newspapers. From the moment he said Bill Walker's name, before he had even begun describing the allegations, I was weeping, for I knew I was about to learn things about my idol that I did not want to know.

Charisma can be a dangerous thing. Put in the service of a higher purpose, it can lay the groundwork for policies and projects that make the world a better place. But the charismatic individual can also be caught up in the magic of his or her personality, come to view herself or himself as somehow immune to the abuses and mistakes that have befallen so many others.

Bill Clinton had a gift. He was and is a political genius with a personal touch that has brought millions under his sway. He also has a libido, and has apparently, thanks to his gifts, felt like he had free rein to exercise wherever and whenever it stirred. That's how the immense good he could have done in his second term was almost completely derailed by a picayune sex scandal. He got (please forgive the pun) cocky, and the nation suffered horribly. I remember well the moment when I realized he had lied with impunity in his insistence that he hadn't had sex with that woman. It felt not unlike the day I learned Bill Walker was a sexual predator.

That is the greatest problem with cults of personality. It's not that all charismatic leaders ultimately prove to have clay feet: Dan Ogren was, I believe very much, the real deal, possessed of both charisma and character. No, it's that the relationship between leader and follower becomes corrupted by the intense devotion that makes it so dynamic. With a charismatic leader, we're able to do great things; but if that leader stumbles, we're very likely to go down with him or her.

When a charismatic conductor disappoints students, some of them abandon music. When a charismatic preacher's abuses are revealed, some people abandon the church.

I have followed charismatic leaders in many of my jobs. It's not easy. People can't help comparing their previous pastor or teacher to me, and I don't do well in that comparison. I'm an introvert, a quiet person for whom small talk is difficult, who has to be extremely intentional in a conversation in order to draw something out of the other; and if that other happens to be a fellow introvert, not given to copious sharing, it can be a very short meeting. I do preach well--I learned from some of the best, including Bill Walker, more's the pity--and this has carried over to the classroom, where my knack for story telling and for explaining difficult concepts in simple terms can be put to good use; but preaching is not the same as conversing, and it's certainly not the sort of thing that makes students thrilled to see me two years after I left a position, and then to write on Facebook that they just met up with the best teacher ever.

I work hard at what I do. I'm diligent and rigorous in rehearsals, working toward a final result that brings the best out of every member of my bands and choir. I care deeply about my all my students, want all of them to succeed individually and collectively. And I want all of them to continue in music long after I'm gone. Should I again change schools, I doubt that any of my Banks students will quit band or choir because they can't imagine playing or singing under any other director. The best testimony I could have to my success as a teacher would be to learn that a student of mine went on to be a music major, then a performer or educator. Not to be me, but to continue growing in the love of music that I have striven to nurture within them all.

I don't want to be worshiped. I don't even want to be followed. I want to be transparent, to vanish into the lessons I have taught, so that years from now, rather than remembering me, they'll sit down and play.

Comments

Post a Comment