Divided We Fall

Things are falling apart.

The end of World War I saw the establishment, across Africa, Asia, and even Europe, of new nations created by treaties drawn up by the winners of that conflict. Many of these nations functioned as colonies until the 1950s, when they began declaring independence. The superpowers drawing up their borders paid little or no attention to the territories of ethnic groups, and thus throughout Africa ancient nations like the Ewe found themselves living in multiple nations, often with borders running down the middle of villages. It also brought together groups of people who would not, of their own accord, have formed a state with each other: Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians in Yugoslavia; Christians, Jews, and Muslims in Lebanon; and, in Iraq, Shia, Sunni, and Kurds. Some of these nations were able to establish unity governments, and even to have democratic elections, but for the most part, they stayed intact as long as they did because of the presence of a strongman in the president's mansion. Once that strongman died or was deposed, the unity of the nation began to unravel.

Yugoslavia is no more. The bloody civil war of the 1990s shattered it into seven states. Beirut has never recovered from the Lebanese civil war that began in the 1970s. Going back farther, the decolonized nation of India was just months old when the Muslim nation of Pakistan broke away. In our time, Iraq seems on the verge of dissolving into three different states.

For some, this is vindication: no longer forced to live in peace with their traditional ancestral enemies, they can now form an affinity state, a nation in which all speak the same language, worship the same god, and practice the same customs. For others, such division initiates an identity crisis: the nation they were born into and grew to love, warts and all, under the previous dictatorial government, was blessed with civil diversity. Shia could have Sunni friends, Muslim and Hindu children could play together, Serbs and Croats could be business partners. As long as unity was an essential aspect of nationhood, diversity reigned.

Loss of the dictator, and the arrival of democracy, has sadly almost always meant a shattering of that unity. A Shia Iraqi can say, "I don't want to live in a Shi'ite state! I want to live in Iraq, with neighbors who are Sunnis and Kurds. I wanted my children growing up in that country, not the Shi'ite republic of whatever it would be called. That is, unfortunately, where Iraq appears to be headed.

There are tragedies running through every one of these conflicts, tragedies even more poignant than the partition of families brought on by the arbitrarily imposed colonial borders. Live in peace with people for a generation or two, and friendships grow, partnerships are created, intermarriage may even take place. The shattering of these unity states into smaller, ethnic monocultures either breaks apart these relationships or requires one or the other partner to live as an alien in the partner's country. Two weeks ago, This American Life featured a story about Iraqis who are grieving the loss of a community of diversity.

It is not unusual for commentators to brush off this tragedy, insisting that the unity state was a manufactured entity, that only the anti-democratic strength of a colonial power or a dictator kept such states together, and that left to their own devices, these peoples would never have lived in the same neighborhoods.

Be that as it may, many of these nations lasted for nearly a century before coming apart, and that is plenty of time to form relationships that transcend ethnicity.

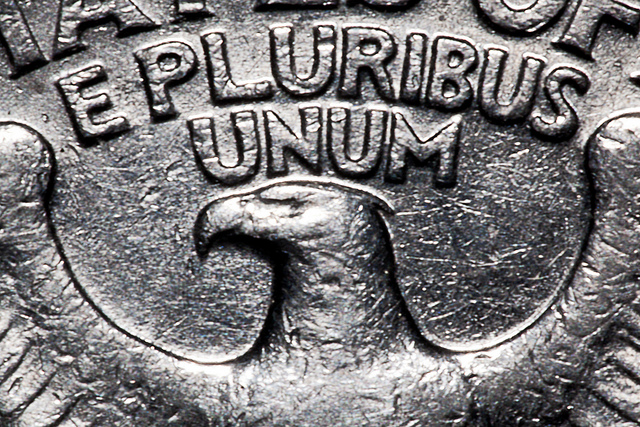

The United States of America, with its founding (though never official) motto E pluribus unum (from many, one), suffered its own unraveling in the 1860s. As with the post-World War I unity states, the nation had managed to hold together for several generations, only to find itself splitting over cultural, economic, and political differences. Unlike the more modern examples above, the USA came back together in the aftermath of the Civil War, in large part because the chief principle of the winning side was not ethnic cleansing, not even the end of slavery, but reunification. The country then imposed on itself a reaffirmation of its Constitutional values. It took another century for the losing states to genuinely capitulate to those values, but it did happen.

And now it is beginning to come apart, Southern conservatives pushing back against the progressives of the West Coast and Northeast. It is highly unlikely that there can be an ethnic civil war in the United States as has come to pass in the Balkans, as is developing in Iraq, and as is festering in much of the European Union, because diversity has, more and more, become a broadly accepted reality of American life. If Americans divide, it will be on ideological, rather than racial or ethnic, lines.

And that will be a tragedy. There was a time when Republicans and Democrats could be friends, when Texans and Oregonians could find common cause, and it was not that long ago. My college friends ran the gamut of ideologies and were as culturally diverse as any group I've belonged to. I have the feeling, though, that if we were to meet in the same dormitory now, we'd be seeking out affinity groups for Catholics, mainline Protestants, Evangelicals, Republicans, Democrats--and simply not come together.

Our nation is coming apart. Ideologues insisting on political purity are pulling people away from each other. The diversity that has been the strength of America--and just as an aside, it's generally accepted that mongrels are hardier than purebreds--is fracturing. I don't know that we'll descend into the anarchy of Yugoslavia or Iraq, but there are frightening times ahead unless we can find common cause once more, overcome our differences, and out of these many ideological splinters, rediscover the unity that is the name of our country.

Comments

Post a Comment