Doing and Being

"Superman is what I can do. Clark is who I am."

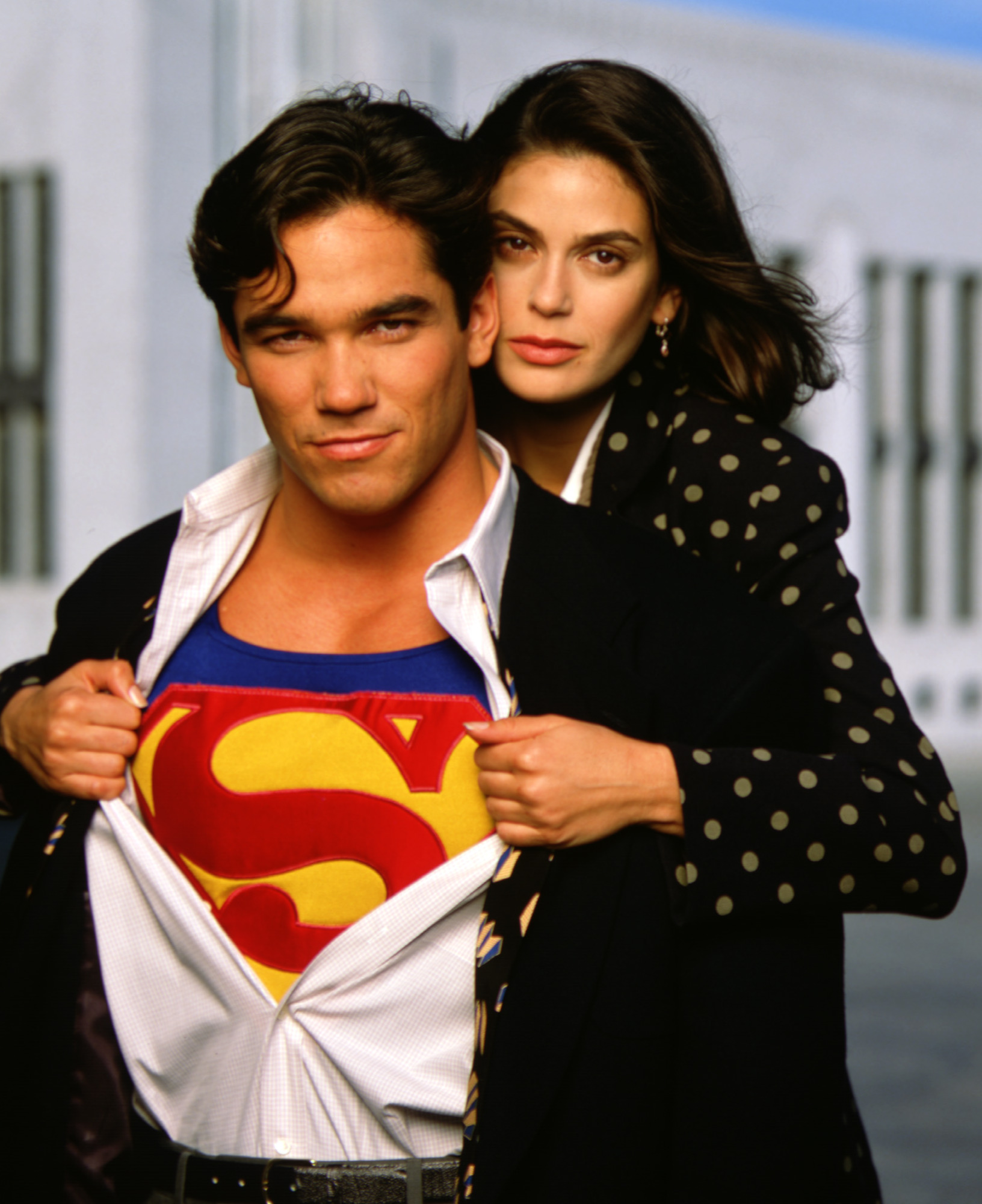

It took Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman two years to get to the great reveal, when Lois Lane was confronted, by a time-traveling supervillain, with a truth she had been denying herself from the beginning: the dweeby co-worker she liked but could not love was the same man as the hunky hero she adored. Put in context, it's comic-book ridiculous; by itself, it's a profound insight that hit me like a Kryptonian punch in the gut. To add insult to injury, I watched this scene play out on TV as I was in the midst of an identity-shredding divorce.

The conundrum of doing versus being is as ancient as human thought: how much of me is in my actions? Am I what I do? To others, there is no other way to know me; and yet, to the extent that my actions are inconsistent with my self-concept, the me they know is not the me I know myself to be.

It's a conundrum for Clark Kent/Superman, too: Clark is a Midwestern nice guy, a deeply moral individual who is polite, unassuming, and appears to be honest in all things; and yet he consistently allows people to believe a fundamental falsehood about himself. As Superman, he stands for truth, justice, and the American way (and by "American way," I mean, without a touch of irony, liberty and justice for all people); and yet, once again, there is a central truth he withholds from everyone he meets. Whether in the business suit or the cape, he is never completely himself--unless, as he puts it in Lois & Clark, Superman is just something he does, a hobby, a persona he puts on like an actor, then leaves behind in the dressing room when he returns to his street clothes and his real life outside the theater.

There is much to be said for the latter frame of reference. As an introvert, I have often found myself putting on an identity for situations that call for me to be sociable, outgoing, gregarious. As a preacher, I often amazed congregations with how forthright I could be in the pulpit--and then befuddled them with how quiet, even terse, I could be shaking hands after the service. I remember one parishioner telling me, "It's like you're two different people."

Yes--and no. From the beginning, I viewed preaching as performance art. The real me--the Clark Kent me--is quiet, thoughtful, circumspect; the super me, on the other hand, could hold a congregation rapt for twenty minutes with moving stories and intriguing twists on Biblical texts. In fact, though, the super was always there. I never stopped thinking those things, and given a soapbox, would happily hold forth on them. But engaging an audience from a stage and engaging an individual one-on-one are two very different things. What was really happening here was that my congregation was making assumptions about what kind of person a narrative preacher must be, and those assumptions were baseless. Yes, I've known narrative preachers who were warm, friendly people in social settings, but I've also known some who were like me.

I've also known pastors, some good in the pulpit, some good in the social hall, some good in every possible scenario, who turned out to be scoundrels: political manipulators, embezzlers, abusers, liars, cheats, sexual predators. The inspiring preacher, the caring pastor, the person everyone loved, was hiding something hideous underneath. It's as if Superman's secret identity was Hannibal Lecter.

It's this disconnect between practice and identity that led me to write this essay. To get back to the moment I first heard "Superman is what I can do, Clark is who I am," I was in the first stages of redefining myself. For eight years, I had been, first and foremost, a husband and father. Preaching was something I did; family man was who I was. In fact, I had confused those verbs, associated doing with being in ways that were, ultimately, harmful to me and those I loved. Raising and nurturing a family is a job. I had worked hard at keeping my performance of these tasks consistent with who I am, with my core principles and beliefs, my identity as one who seeks to do what's right in all situations; but in the last years of the marriage, there had been an unraveling. I began compromising my beliefs in a desperate attempt to keep a dying marriage together. The more it came apart, the harder I fought to hold onto it. And when it finally ended, it was as if I had been stripped of my powers. I could no longer fly, chase down speeding bullets, overpower locomotives. There was nothing left of me but weak, wimpy, timid Clark Kent; and unlike Superman, I had never nurtured my Clark enough to be happy with that.

In time, I put myself back together, and started work on a new, improved identity--but not enough. I rushed into a second marriage, and slipped right back into the same old compromises that hadn't worked for me the first time. They didn't work any better this time around, and after two and a half years, I was again single.

This time I was also out of a job. Now the real work began, as I tried to find a way to use my powers that was, at last, consistent with who I was. It took time, but eventually I found my way into the classroom, became an Orff practitioner, and most recently, discovered Love & Logic. Now when I enter the gymnasium to teach music, when I return home to Amy, when I visit with my children or my parents, everything I do is in harmony with who I am. There is no disconnect between my doing and my being.

And who, you may ask, is the real Mark Elam Anderson? After all these years of building up, breaking down, rebuilding, breaking down again, rebuilding yet again, over and over, I think I've finally figured it out: I am, always have been, always intend to be, an honest man with a big heart. I haven't been successful in this identity--there have been times when I lied to myself, withheld important information from people I loved, closed myself off from people who needed me to care--but at root, it's me.

When Clark says to Lois that Superman is a thing he does, but Clark is who he is, he implies something wonderful: Superman is not just a strong man. He's a good man. With his powers, he could easily rule humanity. Instead, he serves it. He doesn't get that from the cape. He gets it from Clark.

We all have powers. The temptation is to use them to exploit, to victimize, to avenge, to aggrandize. Embracing our inner Clark, though, we can put those powers in the service of the betterment of the people around us and the world we live in.

May all your doing and being be harmonious; and may you be truly super.

Comments

Post a Comment