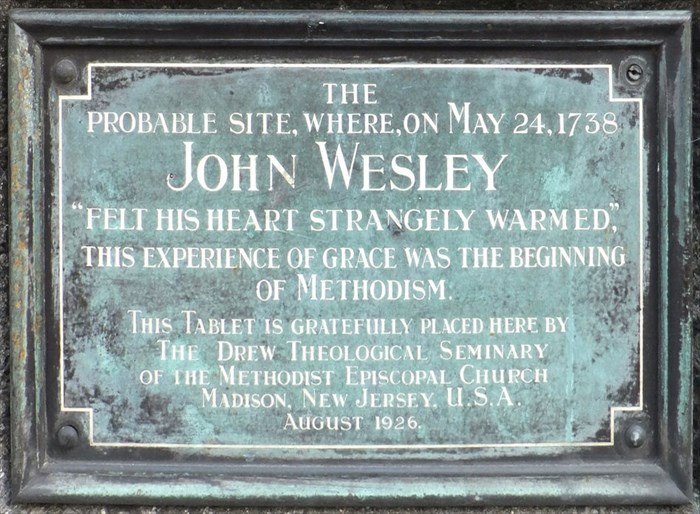

Dispatches from Ghana IV: Strangely Warmed

As a Methodist, I’ve always been equal parts amused and

embarrassed at the words John Wesley used to describe his conversion

experience, which happened in an extremely odd way. Following a failed

experience as a missionary to the New World, during which he behaved abominably

toward a woman who rejected his advances by denying her communion, Wesley had

been sent home to England. His faith at a low ebb, he was wandering around town

when he overheard a Bible study leader reading the preface to Martin Luther’s

commentary on Paul’s letter to the Romans, and dropped in. Something about

Luther’s words affected him so that, as he put it in his writings, he felt his

heart “strangely warmed.”

This language never did much for me, though in retrospect, I

realize Wesley was much like me: a scholar of religion who knew to much to be

drawn in by simple appeals to emotion, whose critique of the Church of England—his

mother church—had led to his expulsion from all its pulpits, and who spent his

entire life searching for some assurance that God actually loved him. Wesley

eventually found comfort in community, as he developed his church within a

church (to his dying day, he refused the wish of many of his followers to formally

schism from the Church of England) around small covenant accountability groups.

He also traveled incessantly, never marrying, living the simple life of an

itinerant preacher into his 90s, his only concession to age the decision to

travel by buggy rather than horseback.

For all the kinship I feel to Wesley, I have increasingly

grown apart from the people called Methodists. Some of that separation is

theological: I simply know too much about the origins of church doctrines, not

to mention the ways in which the inner workings of the church fall short of its

ideals. And as I’ve written many times in this space, I have several bones to

pick with Christianity, not the least of which is its stubborn insistence that

it is the one and only way to salvation. Most Methodists I know shy away from

this belief, but as with all churches, it’s burned into the passion that gave

birth to the denomination: the founding mission statement of Methodism calls

upon “all who are fleeing the wrath to come” to attend to the importance of

being “perfected in love.” The twin directives to avoid damnation and to love

one’s neighbors gave Methodists—as with almost all denominations of

Christianity—its missionary edge. Often that focus was interpreted as requiring

a conversion not just of faith, but of culture, and thus many a rich indigenous

people found themselves subsumed by whichever European nation colonized not

just their souls, but their language and customs.

Missionaries were on my mind last Sunday as Kofi gave us a

short version of his religion talk. The occasion was preparing us for an

experience I was partially dreading: attending a traditional religious

ceremony. Four years ago, when I first visited Dzodze, it was this activity

that most highlighted how foreign I was to Ghanaian culture. Indigenous African

religion is, as Kofi puts it, an “experienced” faith: there is a belief in God,

but with it a sense that the Creator is too busy to be bothered with human

requests. Instead, people honor and pray to God’s assistants, spirits akin to

patron saints who have very specific responsibilities, and may include one’s

ancestors. There’s no one set of rules or dogmas, no received text, just the

experience of worshippers whose drumming, dancing, and singing can often

trigger a trance state. One of those trance states I witnessed four years ago

frightened me, though as Kofi assured us, the mothers of the community rushed

in to protect us visitors from his more extreme behaviors.

In any event, I approached this ceremony with some

trepidation. As before, we were all given long swaths of colorful fabric to

wear over our clothing, toga-style, and given seats of honor. We were, of

course, also welcomed with that uniquely Ghanaian greeting, “You are welcome,” miyawezo in Ewe, the correct response

being yo (a combination of "okay" and "thank you"). As with every

Ghanaian celebration or ritual, music featured a prominent role in this one, with

the drums playing constantly. A woman with a role similar to that of a cantor

led songs and chants, and dancing was constant. Several participants—all women,

but then, in this gathering, the only men were drumming (as in many Christian

congregations, indigenous Ghanaian faith communities predominantly consist of

women)—went into trance, with the mothers of the community making sure they did

not hurt themselves, and eventually ushering them into the shrine where they

could communicate with whatever spirit had triggered the trance. At one point

in the service, there was a break to pass the peace.

In short, apart from the trance state (something I’d

probably be much more comfortable with if I was a Pentecostal), I found much

that felt familiar. This was a marked contrast from my earlier experience.

There was one more big difference awaiting, though, and it took me completely

by surprise.

I wasn’t, I hasten to add, surprised that we were all

invited to join the slow dance circling the center of the hut: such community

dancing is a common feature of Ghanaian celebrations. What got me was being

inside the singing, rather than outside looking on. Ghanaians are not shy

singers. They are not always on key—in fact, they rather like the twanginess of

what Westerners consider bad intonation—but what they lack in pitch accuracy,

they more than make up for in projection. It’s a singing style they have in

common with many ethnic singing styles, and it packs a punch.

The sound of people singing together always moves me. When

it’s children, it can bring me to tears. When it’s adults singing powerfully in

harmony, it taps into a part of me that usually goes hungry: my deepest

spiritual self. Moving slowly around the hut, in rhythm with the drums, as

these women sang powerfully about their faith, I found my heart—there’s no

other way to say it—strangely warmed. Like Wesley, I found myself suddenly

trusting in the love of the Creator, channeled through these generous, sincere

people. I was so visibly shaken by the experience that several of my IBMF

companions asked if I was all right. I’m wonderful, I told them. Really, truly

wonderful.

So that was one religious experience. Another came the next

day, when I participated for the first time in a singing circle, a group

improvisation form pioneered by Bobby McFerrin. Here I experienced the power of

creative community as I never have before. None of us held back, pouring

ourselves into the singing and the body sounds we were making to accompany it.

All had time in the center, soloing over the intricate musical layers. Over the

next several days, I participated in three other circles, and each time I

gained more insight into what works in that context—and what does not. The

first one was a revelation. I tried explaining it to my Orff mentor, Doug

Goodkin, who was with us for half the week, but couldn’t seem to put it in

words that made sense to him.

Which is why I know I’d had a religious experience. This is

a phenomenon I’ve encountered before, whether it was following the only altar

call I ever responded to (at a Black Methodist church in Dallas), or the voodoo

inspired chanting circle I participated in at the Reconciling Congregations

Convocation in 1993. Religious experiences are hard to explain. Theology is

not: I can go on at length about any church doctrine, telling you where it

comes from, why it does or does not make sense, and how it relates to other

doctrines. But describing an experience like either of those I had in the last

ten days, both music related, both very much a part of being in community with

my fellow participants, is a far more challenging proposition. The revival

experience is something that has to be shared, rather than described. It’s the

reason I still feel like giggling when I hear about John Wesley’s strange

warming. Seriously, John? The preface to a commentary did that to you?

And yet, that’s exactly why Methodism took off: a religion

that was both received and experienced. Many who heard Wesley preach found themselves

strangely warmed by what he had to say. Reading his sermons, it’s hard to

imagine why: they’re dry, wordy, intellectual, jammed with scripture references

strung together to prove his point.

Perhaps you just had to be there.

Comments

Post a Comment