Failure to Empathize

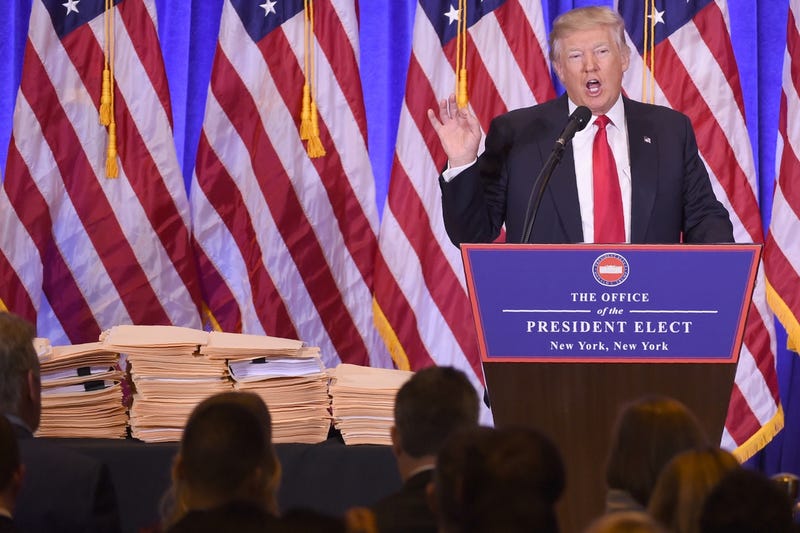

The overabundance of flags, the pretentious sign on the podium, the table filled with (most likely) bogus documents, and most of all, the man himself--Lord help us.

I never see it coming.

It happens like this: I'm teaching a music class to kindergartners. They're deeply engaged, enjoying the story I'm telling, learning the rhyme we'll be turning into a percussion piece, playing the game I've just taught them. And then something happens: I child gets bumped by a classmate, doesn't want to partner with a neighbor, is told "I'm not your friend anymore." Those are the minor causes. Sometimes it's a child suddenly remembering she misses her dead daddy, or that his parents are breaking up. Whatever the cause, it's not something I can preempt, and now I've got a crying kinder on my hands. There may or not be sobs; sometimes (and these are the hardest ones for me to take) it's just tears streaming down a silent face.

Then comes the magic: as soon as the tears are detected, the weeping child is enveloped in a cloud of empathy. The lesson grinds to a halt as I make my way into the huddle, separate the weeper from all the other little people trying to hug their grieving classmate, and figure out what triggered the tears so I can address it. If I'm lucky, the emotion can be diverted through a pat on the back and a promise that the coolest instrument will be in this child's hands in the next rotation, and then the lesson can resume.

When this happens, I'm torn between the standard teacher frustration of having to break the flow of the lesson and a sense of wonder at how naturally empathy comes to a 5-year-old. Kindergarten is on a 4-day rotation through music, meaning I see most of these children just once a week, so I've got very little time to get a concept across to them. At the same time, though, I have to admit that being able to keep a steady beat--something we'll keep working on through first grade, and well into second grade--isn't nearly important to the development of these children as learning to empathize and act compassionately.

And yet, I'm not sure it has to be taught. My consistent experience as a teacher has been that small children can switch effortlessly from angry selfishness to sincere compassion. Narcissistic meanness, on the other hand, grows as children mature, peaking in the teen years. Even then, though, it's not uncommon to see young people overcome with empathetic sadness for a traumatized classmate.

How does it happen, then, that so many adults appear to lose their ability to empathize?

All around us are people in need: hungry, homeless, debt-ridden, sick, disabled, marginalized for factors beyond their control that make them different from the norms of American culture. There are people who dedicate their lives to caring for the needy: nuns, pastors, social workers, activists, missionaries. There are others who donate money, resources, and time to alleviate some of their suffering.

And then there are people who just don't care or, worse, engage in a primitive moral theology that blames all victims for their dire situations. The reasoning goes like this: everything happens for a reason. So you must have done something awful to wind up like this. God/Allah/Karma is punishing you. And who am I to get in the way of cosmic justice? More than that, why should my tax dollars go toward helping you out of this mess that you got yourself into?

You'll note that this mode of reasoning gives a ready excuse for failing to empathize: the poor and oppressed are simply sinners receiving their just desserts. It also lays the groundwork for the Republican party's most ingrained justification for neglecting the marginalized: if they got themselves into this boat, it's not our job to get them out. And for those who still empathize with these victims of their own making, there's one more nail in the coffin of compassion: helping them out could, in the long run, be dooming them to even more suffering. Only through hard work and self-motivation can they hope to attain redemption. It's the old bootstraps trick: if you don't learn to pull yourself up, then you'll always be dependent on the dole.

That's how compassionate conservatism operated through the 1990s and into the Bush II era. It went hand in hand with the excoriation of liberalism as a bleeding-heart approach to social ills, and was so effective that Clinton-era Democrats stopped using the word, opting instead for "progressive." With the election of Barack Obama, however, the compassion gloves came off: here was a President who could do no right in the eyes of conservatives, in large part because of the color of his skin. He wasn't their President. White antipathy for him was quickly associated with the policies he sought to promote and implement. The Tea Party movement grew out of this anger toward people of color who no longer knew their place. The white working class had suffered some hard economic blows, in part from the economic collapse brought on by Bush era policies, but also because the global economy was shifting away from American manufacturing. Neither of these trends was the fault of the new Black President, who actually spent most of his two terms working to dig the nation out of the hole his predecessor had put it in. But he was different: he looked different, he talked different, he thought different.

Empathy is about feeling commonality. Kindergartners feel each other's pain because it's so easy for them to say, "Me too." If I was knocked down the way you were, I'd be crying too. If my parents split up, I'd be scared and upset too. Making that association makes it that much easier to reach out in concern, across superficial distinctions of race, language, ethnicity, or creed.

The fury of the Tea Party was grounded in rejecting commonality, and focusing on distinction: those in power represented a liberally educated elite, far more diverse than the ranks of the opposition. Tea Partiers felt no kinship with Democrats, and Republicans were happy to exploit that antipathy, to stoke the fires and ride the conflagration all the way to overthrowing Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. Once there, they continued to play the antipathy card, refusing to cooperate with the Obama administration, holding out for a Republican to take his place. Had their proposed policies in any way modeled compassion for immigrants, minorities, or the poor, they would have lost the hard edge, so instead, they had to become opponents of empathy. The possibility that a handful of individuals might exploit a social program were grounds for ending it, even if it meant condemning millions of Americans to hunger, homelessness, and losing the health care they had only recently received under the Affordable Care Act. Righteous indignation at the misdeeds of the few trumped compassion for the many.

I used "trumped" intentionally, because this Republican Congress laid the groundwork for Donald Trump to scratch his way into the Oval Office by reigniting the anger of white voters against those different from themselves. Trump campaigned against empathy, welcoming the support of racists, sexists, and xenophobes. The economic benefits of open borders were rejected in favor of a narrow nationalism. Trump's policy proposals were aimed exclusively at his base of angry white men, whom he encouraged to focus on their own frustrations, rather than on the needs of the nation as a whole.

The steady drumbeat--I almost typed "Trumpbeat" there--of vitriol has tainted the nation's spirit. Trump in victory has been uglier than he was on the campaign trail. Winning is everything to this man, and his followers have eagerly embraced that ethic. Perhaps it's the result of an evolving global economy that has, for too long, cast them as losers; but it's an ugly thing to witness, especially for those of us on the receiving end of the gloating.

Which brings me, again, back to empathy. Empathetic winners don't gloat. In fact, as good as it feels to succeed, when success happens in a competitive environment, it always comes at the expense of others. Knowing that others are losing, it's very hard, if one has any heart at all, not to feel their pain. I was thrilled to get the job I now have, but I knew from my years of experience not getting jobs like this how hard it is to be on the losing end of an interview. This led me to feel awkward in the company of colleagues who, I knew, were themselves struggling to find a better job, any job, in a profession that has an embarrassing surplus of skilled applicants vying for a paucity of openings. I wanted to celebrate at this success that came after so many years of longing, but I couldn't help feeling their own fear and disappointment.

That's how my students are, to get back to them, especially the youngest ones. Children wear their disappointment on their faces, and even in the midst of victory, they're quick to comfort their former opponents.

I hope that will always be the case. Lately, though, I'm becoming concerned that Trumpism will eat away at the native empathy of children. In the two months since the election, we teachers have all noticed an increase in aggression among our students. There's something in the air that seems to reflect the increased aggression we're seeing on the highway, in the grocery store, at the gym. People who used to repress their more hateful impulses are expressing them openly. And it's rubbing off on the children. At school, at least, we have disciplinary techniques for dealing with aggression, and it's always appropriate to turn it into a teaching moment.

But I worry. In particular, I worry that the name "Donald Trump" is now being used by misbehaving children in the same way "fart" or "poop" would be: to get a laugh from their peers, and in the process, disrupt the lesson. I ignore the word, focusing instead on rewarding children who are on task, separating children who play on each other's goofiness, and occasionally sending an especially disruptive child to the "Alone Zone" to write an apology. But it's in the air.

And now I'm going to bring it back to myself. I find myself suffering from my own failure to empathize--with Donald Trump. Yesterday morning, I was tempted to watch his press conference (it was a snow day, or I would've been much more happily teaching). Instead, I followed it on my New York Times app as reporters live-tweeted what they were seeing and hearing. I was appalled just at this filtered experience. Later in the day, I heard one sound clip--just one--of Trump speaking at the press conference, and had I not been out on a walk in a public place, I would have screamed an obscenity. Had I been watching it on the television, I would've been tempting to put a fist in the middle of the screen.

There's no getting around it: I want to punch him in the face. I heard him reject a question from a CNN reporter, disparaging that network as a purveyor of "fake news," and I wanted to hit him. I'm a pacifist, a tried and true believer in solving problems through dialogue and empathy, and all I felt toward the man was hatred.

What's worse is that I'm feeling it toward his followers, as well. This is problematic for me, because I've spent much of my life living with, being related to, and serving the very rural and working class people who were Trump's core constituency. I sat in their living rooms, listened to their concerns, prayed with them, served them Communion, offered them words of encouragement and inspiration through my sermons, knew them to be good people with big hearts. In the words of Tex Sample, a Methodist theologian I had the good fortune to hear preach on several occasions, they were "oral people": people who might hold conservative beliefs but who, upon hearing the story of an individual who had suffered from those beliefs, could almost immediately evolve out of them. That "oral" nature is handy when one is trying to convince a person to empathize with a young gay man and, in the process, to open their minds to liberalizing church policies on gay participation. It also means, unfortunately, that they are politically mercurial. With his race-baiting and xenophobia-mongering, Donald Trump helped them make a connection between social progress and economic loss. It's a false connection--the loss of mining and manufacturing jobs has nothing to do with immigration, marriage equality, feminism, or political correctness--but that's beside the point. Because they felt it, they believe it.

And because they believe it, I'm beginning to lose my empathy for them. I know life has been hard for them, that many of them have lost friends and family to drug addiction, that they're mourning the passing of a culture that gave them comfort and support; but all I experience when I see the ragged American flags attached to their pickups, see the "Make America Great Again" slogans on their t-shirts and hats, or hear them railing against minorities or praising their narcissistic leader, is fury.

That's right: the King of Antipathy is making all of America--not just the part that voted for him--a bit uglier.

Comments

Post a Comment