High Stakes

I've been thinking about heightening and stakes because, as my last two posts will reveal, I've had enough time in my new position to reflect on what it means to me. The stakes for me, personally, are very high: given my late start (at 42) and the amount of time I've had away from full-time public school employment since that start, there are not many years left to me to prepare for retirement; or, even more significantly, to end my working life on a high note. While most teachers my age are resting on their laurels, looking forward to retirement, employing decades of experience to sail through the most difficult of classes, I'm still building my skill set. I've got plenty of lessons in my repertoire, but this is only my second year working in a high-poverty school (the first was 2003-4, at the very beginning of this adventure), and as adaptable as I am, this learning curve is steep. The improv I do every day--hotwiring lesson plans on the fly, tweaking, editing, working around major disruptions, accommodating the needs of my students and the inadequacy of my space--has extremely high stakes. If I can make it through this year, and end it on a positive note, I'm set professionally, equipped to grow from strength to strength right up to retirement, at which point I'll be well satisfied with my accomplishments. It's also possible I could crash and burn, fail so miserably that I'll be consigned to substitute teaching for what's left of my career, piecing together an income between that and private lessons and performances.

I don't foresee that happening--I seem to be finding the right balance between firmness and compassion, and there's no danger of me running out of ideas--but there is a third outcome that would be worse: playing it safe, backing off from the risky hands-on teaching that is the Orff approach to one in which my students are in assigned seats throughout class, learning about music from books and videos but rarely actually making music. I taught that way for my first two and a half years. I doubt that my students learned much in my classes. I did have plenty of discipline problems, and frequently ended days tired and discouraged. It's the path of least engagement, of sacrificing the students' learning to the teacher's sanity. This approach is not for me, though there are textbook companies making fortunes selling it in brightly colored packages loaded with bells and whistles to school districts across the United States. To me, that's a waste of money: I'd rather be able to put mallets and drums in my students' hands so they can learn by doing than hand them a book, however attractive, that will tell them about it. And it's the path that leads not so much to a burn out as a fizzle out. No, I want to end on (prepare to groan) a high note, and everything that's happened in the last two months tells me I will. I end my days tired, sometimes frustrated, but always exhilarated, knowing I've made a difference, and my students are going home loving music.

As high as the professional stakes are for me, they are dwarfed in comparison to the personal stakes of my students. They go home to situations that are already heightened to the breaking point. Most of them get free breakfast and lunch at school because that's the only way to be sure they're getting enough to eat. Many have absent parents; others have parents who are abusive, strung-out, engaged in illegal activities. There's a high turnover rate: children rarely stay at this school for all six of their primary years, as their parents move frequently in search of work. Some have been pressed into duty as caregivers for younger siblings.

Which brings me to a child I'll call Theo. He's a big bear of a child, easy-going, big smile, friendly, good-natured; he greets me every morning with a grin and, frequently, a vigorous hug. I mistook him at first for a fifth grader, but he's actually in the third grade, though his size makes me wonder if he may have been held back a year. A couple of weeks into the school year, I was outside doing my morning duty when Theo came by. "How are you?" I asked him. "Not good, Mr. A," he replied. "What's up?" I asked. "I'm worried about my little sister. She's home alone." "How old is she?" I asked. "Four," he said. "My mom wasn't home from work, and I had to catch the bus." "Wow, that must be scary for you," I told him. I saw the school secretary passing between buildings at that point, flagged her down, and asked her to look into it, then sent Theo on to class.

I don't know how many of these children have situations similar to Theo's, but I suspect there are many. There are others who, when told anymore disruptive behavior will result in a call home, go instantly from rambunctious to frightened. And then there are those who just can't help themselves, who will probably only fit into an institutional environment when the behavioral symptoms of their upbringings have been dosed with ADHD drugs.

For all these children, the source of their difficulties is something over which we teachers have no control. We're not a private school, so we can't pick and choose students whose parents are fully employed and will partner with us to help them excel, and who meet minimum academic requirements before they're even admitted. The only criteria for being a student at Margaret Scott are address and age. Our job is, if anything, to lower the stakes for them, to create a safe place where they can learn to cope with all the trauma that exists for them when they are not here, and, as a side benefit, to teach them how to read, write, calculate, and express. Their test scores will never rise to the level of children who attend a Catholic school, a charter school, or even a typical suburban or rural school. We have to pour so much energy into just getting them to a place where they can absorb some of what we're sharing that test scores are the least of our worries.

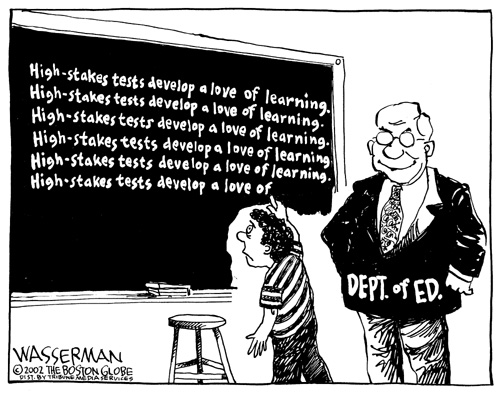

Don't get me wrong, the testing is still there. There's no choice in the matter: every school in the United States is mandated to put every child through standardized testing; and there will be parents attending conferences next week who will be upset when they learn how low their children have scored on some of those tests. The hardest part of those conferences will be helping these parents realize the environmental factors influencing those scores: the distractions at home, the emotional issues affecting attention at school, the class sizes that cannot be helped, the boundary change that has brought a hundred new students into our building. Many of them will focus on social issues: how a child is interacting with both peers and adults, ways in which a parent can help that child fit in better and act out less. Ultimately, unavoidably, the discussions will come back to the test scores, and to lowering the stakes of those scores.

Because as much as politicians value test scores, what we're teaching at Margaret Scott has far higher stakes in the long run: that learning is more rewarding than distraction, that cooperation is better than antagonism, that there are people in the world who care about what kind of adults these children become; that we love and accept them as they are, even as we challenge them to become much more.

Comments

Post a Comment