This Isn't Science Fiction

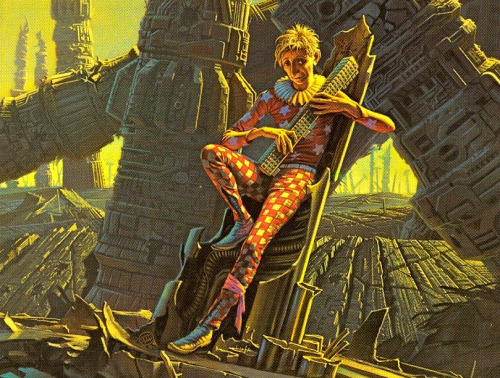

Cover art depicting the Mule from a paperback edition of Foundation and Empire.

― Isaac Asimov, Foundation and Empire

In 1973, Isaac Asimov changed my life.

I was that most pitiful of adolescent types, a lonely nerd in search of a passion. I was mercilessly bullied by my seventh grade peers, had no close friends, and had only recently lost my interest in playing with action figures, but had yet to find anything to take the place of them. I had a knack for writing and some modest musical talent, but neither of these pursuits had become a passion for me yet. My hatred for sports (it was always pre-empting my favorite Saturday morning cartoons) meant I had little in common with other boys my age. As a whole, then, my life was miserable.

Then came the miracle: the public library moved into a brand new building across the street from my father's church in Emmett, Idaho, and Dad suggested I go in and ask for a job. I don't remember any of the details of how this came to pass, but somehow I landed the position of paperback exchange organizer. Every day after school, I'd walk to the library and sort the books on the exchange shelves, an honor-system area of the library where patrons swapped books with each other. I created my own system, grouping books by genres and, within genres, alphabetizing them by author. In payment, I took an occasional book home for myself. One of the first I took was The Naked Sun, a science fiction detective novel by Isaac Asimov. I'm not sure whether it was the provocative title (Naked! Ooh!), the cover art (a man's head with some skin removed to reveal circuitry underneath), or the plot summary that drew me to the book, but once I began reading it, I was hooked.

I'd already been watching Star Trek in syndicated reruns for years, and had loved Lost In Space when I was younger, so it's not as if I was new to science fiction. But there was something about Asimov's writing that grabbed me, and continue to do so throughout my teenage years and well into adulthood. Asimov's writing was style was unsophisticated, his dialogue stilted, and his characters more archetypes than living people--all things I was chagrined to discover in my 40s when I began rereading the Foundation series, long acclaimed as the greatest multi-volume work in science fiction history--but he had a gift for creating worlds that made sense and, more than that, for understanding the enormous forces at work in human history, and projecting them forward into our distant future. In the 1970s, though, I didn't care about any of that--not the lack of literary skill, nor the deeper meaning behind Asimov's plots. What I knew was I had found myself in these books. I was, and always would be, a science fiction nerd.

Those Foundation books--a series originally written as short stories and novellas in the 1940s and 1950s, supplemented and filled out in the 1980s as Asimov neared the end of his life--are to science fiction what The Lord of the Rings is to fantasy. Perhaps without ever realizing he was doing it, Asimov created a political allegory that has become truer with each succeeding generation. And suddenly today, for the first time in a decade (that reread I mentioned earlier took place in 2006), I find I can't stop thinking about them.

Foundation takes place tens of thousands of years in the future. Humanity has colonized the Milky Way, which is now ruled by a Galactic Empire. At the height of the Empire's golden age, a social scientist named Hari Seldon sees troubling trends developing, leading him to create a new science he calls psychohistory. By analyzing sociological and political data, and working it into a general field theory, Seldon is able to predict long term trends. He realizes the Empire is due for a collapse, and that this will be followed by 10,000 years of chaos. He also theorizes that, by creating a secret enclave of thinkers called the Foundation, he can limit the damage of the impending Dark Age to a single millennium.

Several hundred years later, all of Seldon's predictions have come true. The Empire has fallen, and much of the galaxy has reverted to primitive cultures and technologies. Like the great library of Alexandria, the Foundation is holding on, continuing to make progress in the physical sciences. Somewhere else in the Galaxy, a Second Foundation works in secret to guide social trends. Seldon's plan seems to be on track: civilization is making a comeback, and a new, more enlightened empire will rise from the ashes of the old one.

Enter the Mule.

Seldon's equations were all big-picture science, making no allowance for the impact one extraordinary individual could have on galactic trends. The Mule is just such an individual: a charismatic leader who can manipulate the emotions of entire star systems, creating a new empire before the galaxy is ready for it. His movement is brutal and fascistic. As an individual, he is both cunning and mercurial. He has no appreciation for subtlety. He succeeds in conquering the Foundation, and harnesses its advanced technology to expand his hegemony across the galaxy.

I am far from the first blogger to find parallels between the Mule and Donald Trump. But I'm seeing something much deeper than just the disruptive presence of a uniquely gifted individual: remembering the themes of Foundation is helping me cope with the imminent collapse of American exceptionalism.

There was a time when I was absolutely caught up in the greatness of this country. I saw the trends in our history leading us as a people toward equity and inclusion. Even with the setback of the Reagan/Bush years, I felt like we were ultimately on the right track: a beacon of democracy to the rest of the world, a big-hearted, generous country that embraced people of all ethnicities and creeds, and would, in just a matter of years, get over its obsession with sexual purity to become more welcoming to LGBTQ people, as well.

Then came the Persian Gulf War, and George H. W. Bush comparing Saddam Hussein to Adolf Hitler (Hitler came out better in that comparison, by the way). I saw American troops in a fight for "freedom" that was really about protecting oil wells. I saw 100-to-1 kill rations being called "just war." And I saw millions of Americans going along with it, waving flags, turning yellow ribbons into jingoistic symbols of American victory, and I was disgusted by the entire spectacle.

Bush was followed by Clinton. Things looked up for awhile--perhaps America could, again, be a force for peace--but all that came apart with the hypocritical Gingrich impeachment of a President whose misdeeds paled in comparison to those of his prosecutor. A stolen election, airplanes crashing into towers, a hideously bloody and expensive war with no positive result, eight years of relentless racist obstruction of the sanest President we've ever had, and now an election result that mirrors, on the largest and most significant scale imaginable, what's been happening across Europe: the world republic I dreamed of as a young man is collapsing. At the peak of our technological abilities, our civilization is beginning to crumble.

Some of it is that, as in Foundation, an extraordinary individual has come to power, subverting all the norms that had previously made for more peaceful transitions and to far less stomach-churning swings from left to right and back again. But this Mule did not just arrive on the scene out of a vacuum. The trends have been there all along, the simmering power of the right just waiting for the right demagogue to exploit it.

The question for us, as for Asimov's Foundation, is how long our dark age will last, and what we can do to minimize the damage. How much of the structure of our civilization can we maintain, keep in place, so that when the world finally awakens from its xenophobic nightmare, it has a scaffold upon which to rebuild democracy? That all depends on those of us who can see the bigger picture. If we let go of it--if we give into despair or hatred, secede from the union, hunker down and just try to ride it out--it's going to be a very long time before we're once again making progress toward full inclusion. If, on the other hand, we wade in and get our hands dirty, working to minimize the damage, to care for those who are excluded and persecuted, to maintain the institutions that foster respect and human dignity, and to never, ever stop protesting every single step our new government takes toward the darkness--then maybe, just maybe, we can keep this nation from tipping over into the abyss, and the dark time can be limited to a single election cycle.

Asimov was, after all, writing about an entire galaxy, so of course it was going to take centuries, if not millennia, to restore civilization. The world we're hoping to save is considerably smaller. Yes, it's an entire world; but it's all connected by a single internet, and a determined travel can physically circumnavigate in a day. The trends shifting civilization away from democracy involve hundreds of millions of voters--but there are hundreds of millions more (and, in the case of our most recent debacle, those millions are literally more than the opposition) who, given a chance, will shift their nations back away from nationalism, and toward globalism.

We can bring it back. We must bring it back. The alternative is too dystopian to accept.

Comments

Post a Comment