Rural Roots

It's a divide as old as civilization.

A town mouse paid a visit to her country cousin, who served her a traditional country dinner. The city mouse turned up her nose at the humble cuisine, telling her cousin, "You should come visit me in town. You'd be blown away by how rich the food is." The country mouse took her up on the offer, and found that the food was every bit as delicious as her cousin had promised. Of course, this being a town, there were dogs roaming the streets, one of which chased the mice into a hole. "The hell with this!" said the country mouse. "No fancy city food is worth becoming a meal for one of those monsters!" And with that, she headed for home.

Aesop told the story 2600 years ago, but he drew on traditions already ancient in his time. Humans first began to practice agriculture 12,000 years ago. It took another 6000 years for villages to evolve into the first cities. At every stage in the process, there must have been conflicts: hunter/gatherers contending with their pastoralist cousins, who in turn found themselves at odds with the tradespeople congregating in villages, who for their part found the larger urban centers places of iniquity and danger. Meanwhile, people in those urban centers were developing new ways of relating to each other. Networks of trade, municipal services, affinity groups, higher education, cultural expression, religious institutions, and over it all, government: all these innovations contributed to the urban identity as more sophisticated than its rural equivalent.

And that's how Donald Trump got elected.

Whoops, I left something out: the electoral college.

The electoral college is one of the many quirks of American Constitutional democracy. Like so many other American quirks, this one originated as a compromise to bring the country together. From its very foundations, the United States was a nation of nations, thirteen colonies, each with its own identity, with one thing in common: a desire to divorce themselves from the British Empire. Individually, none could have succeeded, but working together, they pulled it off. Then came the far greater challenge of making that initial miraculous victory permanent. The newly independent states bickered for years, initially under Articles of Confederation but then, when that proved too chaotic, by cooperatively drafting and ratifying a Constitution. The states were still at odds with each other: in a pure democracy, the more urban states of New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania would have had more power than their rural counterparts simply by virtue of their higher populations; meanwhile, the more rural southern states created the raw materials that drove the new American economy, and were terrified that urban northerners would end the peculiar institution of slavery that made them so productive. It would take a massive compromise to unite these states, and that compromise was the electoral college. It vested electoral power not in a pure count of the vote, but in a set number of electors for each state, determined by the number of their members of Congress. The system was promoted as a buffer between an under-educated electorate and the nation's highest office: electors would be political savants who could correct a bad decision by the voters they represented, reversing it to keep a corrupt populist out of office. But it never functioned in that way (and certainly didn't yesterday), as the vast majority of electors simply went with the majority of voters in their states.

Practically, the electoral college has had the effect of diluting the urban vote and strengthening the rural vote. In most elections, this has not made a real difference in the ultimate victor. There are, however, notable exceptions, of which none is more notable than yesterday's result.

Hillary Clinton won the popular vote. No matter how Trump's toadies spin the result, 3 million more people voted for Clinton than for Trump. Unfortunately, most of those people lived in California and New York. So she won the states with large cities by huge margins. Meanwhile, she lost several rural states by much smaller margins. Trump eked out a lopsided (though nowhere near landslide) electoral map victory. It's an ugly victory, a victory built on America's fastest-shrinking cohort: a white working class that, in just a few years, will become a minority.

I've written a lot in the last month about the ugly things that election says about America, and I'm far from finished. For the remainder of this essay, though, I'm going to go back to those mice.

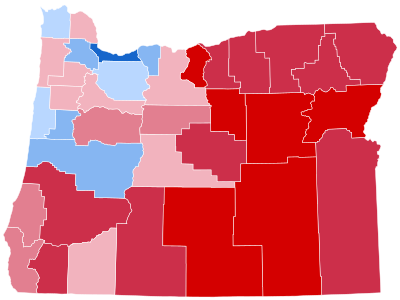

Take another look at the map of Oregon at the top of this page. It breaks down the 2016 Presidential election by county. The darker the color, the larger the majority for Clinton (blue) or Trump (red). There's no getting around the fact that Clinton's votes were concentrated in the northwest corner of the state. The purest Clinton vote is in a single county: Multnomah, home of Portland. Hood River and Benton counties come next, Hood River by virtue of the arts colony from which it gets its name, Benton thanks to the presence of OSU and the progressive small city of Corvallis. The left-wing paradise of Eugene, though, is not enough to darken Lane county beyond a very light blue; and Washington county, where I live, is similarly light in its blueness.

What can we learn from this map? That there are a hell of a lot of country mice in Oregon, and the city scares the bejeezus out of them.

I've been hearing about this divide for as long as I've been an Oregonian. As a high school and college student, I remember my classmates speaking disparagingly of Portland, and how unfair it was that this one city had so much power over the rest of the state. I heard more about this from my parishioners when I returned to Oregon as a rural minister: the Methodists in Portland have far too much say in how we do things here at Podunk UMC, they'd tell me. This rural resentment for Portland led to the movement, dating back at least to 1941, for southern Oregon and northern California to secede from their respective states and create a new, more conservative state called Jefferson.

I grew up in small towns in California, New Hampshire, Idaho, and, finally, Oregon. I remember traveling with my parents to visit cities and feeling overwhelmed by their scope and complexity. Boise felt huge to me, Portland mind-bogglingly enormous. These were frightening places marked by heavy traffic, crowded sidewalks, and criminal activity. It was so easy to get lost, to wander into a scary part of town. I knew I didn't belong, and worse, knew that the predators around me could tell that about me. It was just a matter of time until I was victimized, swindled, mugged.

That was me before Dallas. Prior to beginning seminary in 1985, the largest city I'd actually lived in was Salem, Oregon (population in 1980: 89,233), where I attended college. I'd visited bigger cities, even driven some in Portland, but none of that had prepared me for life in a real city.

Dallas changed me. It was huge, busy, frantic, and had no patience for the tentative driving manners of a hick like me. I had to adapt if I was to survive: none of my many off-campus jobs was accessible by Dallas's ridiculously inferior public transportation system. I also discovered that big cities have more cultural opportunities than even a big town like Salem can provide. Three years after starting seminary, I moved to England for two years of ministry in a suburb of Manchester. Now I had old European cities to explore, cities that had not been as intentionally engineered as American cities. Take a wrong turn in Edinburgh, and you can't count on a street grid to get you back on course. I came to find this chaotic infrastructure charming, wondering what the original purpose of an ancient road had been that led it to wind so haphazardly around a community.

Coming back to Oregon was a return to my youthful roots: once again, I was living in small towns, enjoying the cozy familiarity of rural life. Except I didn't really enjoy it: whenever I could, I headed into town to shop, eat out, take an urban run. Portland, I now realized, was not that big a city after all, and its street grid made it easily navigable. Better yet, I now knew, Portland's political identity was much more attuned to my own than that of any small town could ever be. I was transitioning from country mouse to city mouse, and I liked it. No, scratch that: I loved it. Sometime around 2001, I realized I was no longer a small town boy: I belonged in the city.

Since then, I've lived in and out of the Portland city limits. While I technically have a Portland address now, my home is actually located in unincorporated Washington county, in an area that is being transformed by developers from farmland into suburban neighborhoods. It's still easy to get from my street into the country, but that won't last. There's a lot of earth being moved on Kaiser Road these days, as farm after farm is transformed into residential properties.

The continued presence of those farms is what has kept Washington county light blue. A map breaking down the county by precinct shows some of them to be as bright red as any county in eastern Oregon. I don't have to travel far to be in the presence of country mice, and to see the signs they put up on their property decrying the development going on all around them. They're afraid of the future, and any candidate who promises to preserve or, better yet, restore the rural life they used to know is going to receive their vote.

That's the ancient divide that still dictates politics not just in my county and state, but in the country as a whole. We can talk about scrapping the electoral college; we may even someday find a way to do it; but that will not eliminate the reality that some mice belong in the country, others in the city. As a rural pastor, I served people who spent their entire lives within a few miles of their birthplace. They were suspicious of the city, terrified of its busy complexity, and quite content with the handful of retail and service choices in the county seat. There was no need to drive into the city.

Washington, Oregon, California: none of these states gave a single electoral vote to Donald Trump. And yet, all three of them share the divisions of the nation as a whole. It's why we can't really break away and form a liberal ecotopia. Too much of the bounty that makes our economies boom is produced by our rural counties, places that are, by and large, quite happy with the result of the 2016 election. If we're going to move forward as a region, let alone as a nation, we've got to find a way to bridge this divide, to get mice of every persuasion to mutually appreciate one another.

It's not going to happen if we continue to demonize the opposition, to belittle them from our lofty culturally elite perches. We've got to get in touch with our common humanity, our shared concern for the wellbeing of those we know and love. We've got to listen to them as they share their fears and insecurities with us, empathize with them over the trauma of widespread rural drug abuse, acknowledge that not all urbanization is good. Perhaps we can find common ground in the ground itself: most of the most beautiful parts of Oregon and, beyond this state, the United States of America are in regions that voted very solidly for Donald Trump.

I love those places. I want to be able to go on visiting them without becoming furious every time I see a Trump bumper sticker or baseball cap.

But it goes deeper than that: as much as I love living in the city, my roots are in the country. Those are my people. I belong there, among them. And no hate-spewing developer turned politician is going to take that away from me.

Comments

Post a Comment