Decline, Fall, and Apotheosis

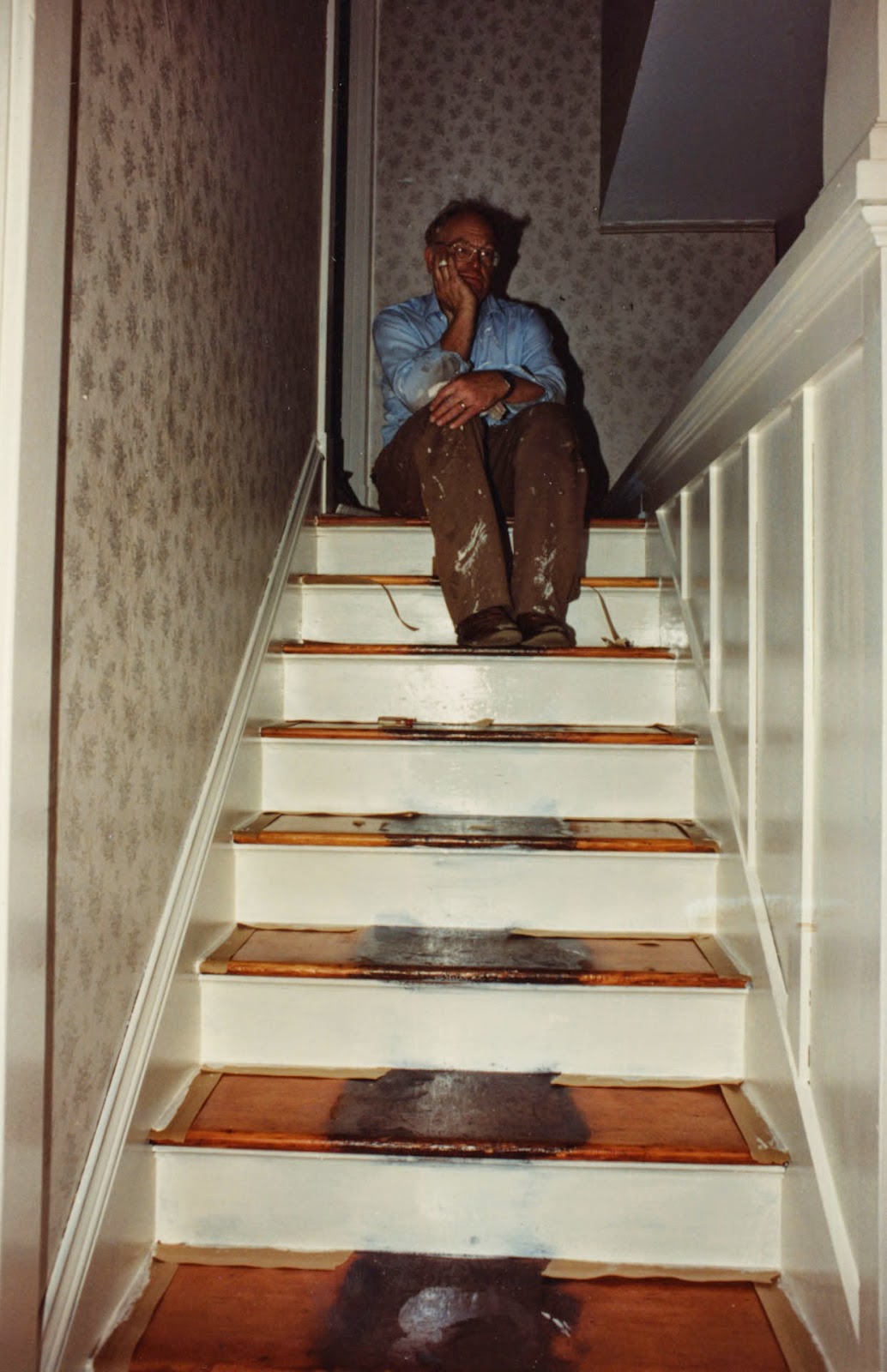

1990: the remodel of the front staircase nearly complete, my father rests from his labors.

You don't know Elam.

Please don't be hurt by that statement. I don't know if anyone ever truly knew my father. Despite being deeply, sincerely compassionate, he was a thoroughly private man, only sharing his feelings when he believed it was vital to communicate a matter of extreme importance. Some of that was, I think, cultural: the grandson of Swedish immigrants, I suspect lagom, Swedish reticence, ran deep within him. Another part of it was generational: prior to the 1960s, men were not raised to be publicly emotional, and people in general valued their privacy to an extent later generations would consider harmful. Finally, as much as he enjoyed conversation, I think my father was more introvert than extrovert. He worked best in a quiet space, by himself, and never complained about alone time.

I know from personal experience that introverted pastors have a very hard time winning over congregations. Whether visiting in an emergency room, a parlor, a fellowship hall, or the "Nice preach, Rev!" line after the Sunday service ends, a pastor is expected to make every person he or she comes face to face with feel that here, at least, is my best friend. Successful pastors do this with ease, especially if they're naturally extroverted. Introverts can learn to do it, but in my own experience, it feels forced, insincere. I suspect that's how it was for my father, too, and it's probably why he changed appointments so often, and why, despite living after retirement for almost 25 years in McMinnville, he never really connected with that community.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. The next thing I say, the most personal thing I can say, I've already said: I didn't really know my father. This saddens me, because I believe he wanted me to know him better, but just couldn't find the words to express that to me, though he did write to me several times once I reached adulthood about how the distance he sensed between us grieved him. It's not that he was a mystery to me: I knew many things about him, could predict how he'd react in a variety of situations, understood many of the difficult decisions he made. I knew, for instance, that, however hard ministry was for him, he stuck with it because, living as close to the financial edge as our family did, he knew we could never afford the years it would take him to retrain for a different profession. It's the same rationale that kept me in ministry long past the time when I realized I wasn't truly suited for it--though in my case, the church ultimately eased me out, as gently as it could, but decisively, and with no room for protest on my part.

A steady diet of hard choices and disappointing results had to take a toll on him. When I was a freshman or sophomore in high school, I learned from Mom that Dad was going to have a procedure to screen him for cancer. For two days, I couldn't think about anything else. Sensing my fear, Dad came up to my room in the middle of the day (I was home sick from school), and told me he'd had the colonoscopy, and that a few polyps had been removed, nothing to worry about.

And yet, as routine as that might have been (though I'm not sure how routine it was in 1976), it was, for me, the moment at which my father transitioned from being a powerful man of action to becoming an older man with health issues. Three years later, my first semester of college was interrupted by Dad's first small stroke: he'd started seeing double, and had tried to keep it to himself, apparently driving with one eye closed. In the end, he had to tell Mom, who insisted he go to the hospital. I got on a bus and traveled home from Salem to Harrisburg where, for several days, I had a knot of anticipatory grief in my gut. In the end, tests revealed nothing out of the ordinary, and double vision corrected itself, and Dad returned to work. In the years that followed, though, he had more incidents like this one, often repeating the pattern of keeping it from the family. These were, it seemed, connected with stress in the workplace: arguments with church members who opposed his openness to socialism, gun control, evolution. With retirement came the hope that he could let such conflicts go and, in the process, outgrow the tiny strokes that were causing the vision issue.

For two years, that appeared to work. Dad threw himself into renovating the house in McMinnville, polishing floors, swapping out appliances, creating a kitchen island, papering and painting the walls, installing new light fixtures, turning a closet into a shower room, and transforming the huge back yard into a productive vegetable and fruit garden. Finally he had a life of tangible results, along with the security of a home that would be his as long as he chose to remain in it.

And then he had a heart attack.

It was June, 1992. An angioplasty cleared the obstruction, and Dad was soon out of the hospital, back home, taking walks, eating a low-fat, low-salt diet, and apparently as good as new.

Until New Year's Day, 1995, when he had a real stroke.

As I noted above, he'd been having little ones for years that mostly affected his vision. This was different, weakening one side of his body and partially paralyzing his vocal cords. He fought back from this one to the point that, while he was slower, especially on stairs, he seemed physically to be almost his old self. It was his voice that never recovered. The preacher was not silenced, but the singer was. For the rest of his life, he sounded like a man with laryngitis. Eating--something he had always relished--also became much more difficult, frequently interrupted with coughing spells as he aspirated some of his food.

Bit by bit, incident by incident, my father was becoming elderly.

Despite these challenges, he remained active, attending ministerial association meetings where he tried to get all the churches in McMinnville to cooperate, traveling extensively with my mother, squeezing all the enjoyment he could out of retirement. As he turned 80, he was as happy and fulfilled as I can remember him ever being, taking all his growing physical limitations in stride.

And then he fell.

It was November, 2006, and he was at the public library looking up and printing out an image for a Christmas card. Getting up from the carrel where he was working, he caught his foot in the cables under the desk and went down hard on the inadequately padded carpet that covered the concrete floor. His hip was broken.

The eight years that followed were increasingly hard for him, perhaps harder for my mother, whose role had to evolve from dietary watchdog to full-time caregiver. He had surgery on the hip, physical therapy, was in and out of rehab facilities, learned to walk, very slowly, with a cane, but never regained enough mobility to leave the house. He was also now in his 80s, and his body began to wind down. Cursed with a redhead's low pain threshold, he cycled through medications as doctors struggled to balance toxicity with relief. His skin thinned, his joints eroded, his organs became weaker. He had more coronary incidents, more strokes. He was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. Hearing loss coupled with growing mental confusion made conversations with him extremely challenging.

Perhaps the biggest blow to him was the emptying of the driveway. I remember a day when he tried to prove to me that he could still manage coupling the travel trailer to the car by himself--and failed his own test. My parents' days of travel independence were over. There would be no more driving vacations. Not long after that, my brothers and I finally got him to surrender his car keys, as well, though this was, for him, more about how hard it had become to get in and out of the driver's seat than about safety. It was not long after this that he had to give up the upstairs bedroom. We moved the double bed down the stairs to the den, where it stayed until he transitioned to a hospital bed and a wheelchair.

Toward the end, he was able to get out of the wheelchair for a daily circuit of the house with his walker, but we could all see, to use the Biblical cliche, the writing on the wall. The night before he died, he literally saw writing on the wall, a plaque he couldn't quite make out, visible only to his delirious eyes.

And then he was gone.

Macy and Sons, the McMinnville funeral home, did a fine job of restoring his dignity for us without enbalming or cosmetics. Two hours after he had been pronounced dead, I saw him lying in his hospital bed, the covers pulled up, his eyes closed, appearing to be peacefully asleep. A few hours later, I saw him at the funeral home, now wearing a shirt, his hands folded. Two days later, I visited his body for the last time, and saw him now dressed in his preaching robe and stole, in which he was cremated sometime later. Despite the illusion that he was sleeping, that his chest was rising and falling, I knew he was gone. His struggles were ended. Whenever I'd seen Dad napping in those last years, he'd been on his side, folded up almost into a fetal position, and I'd felt pity at how vulnerable he appeared. No more: all the pain, all the worry over what part of him might next give out, was over. He wasn't the man I remembered him being in that robe, standing tall in the pulpit, exhorting his tiny rural congregations to open their hearts to God and their minds to the needs of the world around them; but he was very much the way I needed to remember him now, at the end of his earthly journey.

A week ago, at a far-too-sparsely-attended service, my brothers and I, with some help from my daughter and a few others, spoke at great length about our father. We displayed tokens of his life and beliefs: the Chinese symbol of heaven, the stained glass character "An" (peace or tranquility in Mandarin) he had made, his Scout merit badge sash, his Master's hood. We showed slides of his life and work, sang songs from his autograph hymnals, handed him off to whatever spiritual forces usher us out of this life and into whatever follows, and did it with joy and sadness. Then we went home to the house where he spent his last quarter century and continued to share. The concentration of stories and memories in the last two weeks have given me something I never had while Dad was alive: a sense that I am, finally, coming to know him.

The one form of immortality even atheists can aspire to is the way we live on in our children. Whether or not there's a heaven, any human who has lived a good and faithful life finds apotheosis in those who remain once he or she is gone. My father lives on in his wife, his sons, their partners and spouses, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. As the years pass, those who follow will find it more difficult to attach his name to his influence, but it will live on, just the same. When, in a hundred years, some Anderson descendant has the flash of insight that earth's crammed with heaven, that the blackberry growing through the fence from the neighbor's unkempt yard contains within itself everything one needs to know about the goodness of Creation, Pastor Elam will be a part of that moment. That this hypothetical great-great-great-grandchild may not think to put the name "Elam" on the insight is irrelevant. Name recognition never mattered to Dad. It was always enough for him to know that he'd made a difference. In fact, the man I know more fully now than I ever have would simply rejoice in another soul being touched by the immanent ineffability of God.

That's the paradox of this moment: that it takes death to weave together the strands of a life lived well into a tapestry that can do it justice. I hope the words I have written about my father have, in some way, given you a sense not just of who he was, but who he is even now becoming in me and mine. In the words of the funeral ritual I spoke so many times, "Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord. Henceforth, says the Spirit, they rest from their labors, and their works do follow them."*

Amen.

*Revelation 14:13

Comments

Post a Comment