Making Musical Medicine Palatable

Bad boy classical violinist Nigel Kennedy.

The popularization of classical music has been going on for a very long time. I remember watching a Leonard Bernstein children's concert on PBS when I was in junior high. Bernstein was talking about Beethoven's sixth symphony, and trying to remove the associations his audience had with the imagery of Fantasia. Since I had never seen Disney's early foray into producing animated images to accompany classical music, I had no idea what Bernstein was talking about--though his effort to make this lovely piece of pastoral music interesting to a young audience was well-intentioned, and I stayed tuned in to listen to the performance.

Serious music has always had a hard time finding an audience. Music historians are fond of talking about how Mozart and Beethoven were the rock stars of their day, but they exaggerate the popularity of these great musicians. Mozart died in poverty, and Beethoven had to sell the same compositions to multiple publishers to stay out of poverty. Performances by either could generate large audiences, but the most popular music was that which was made in dance halls and living rooms: simple, danceable, singable, and easily performed by untrained musicians.

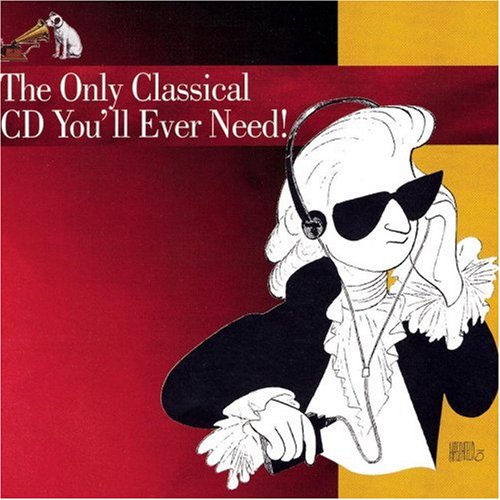

Understanding this, serious composers often created more accessible works: suites of dance music, program music, incidental music for theatrical productions, variations on folk songs--all of which were viewed in a utilitarian light as something to pay the rent and free up the composer to write more rewarding, but less lucrative, serious works. Today, many of these composers are only known for their lighter pieces, works that would someday appear on albums like this:

Or this:

Some composers created vast quantities of music, much of it magnificent, only to have their entire careers reduced to single pieces that made it into the pops repertoire. Some examples: Opera giant Rossini, known for the overture to William Tell; Mozart for the first movement of his divertimento Eine Kleine Nachtmusik; Beethoven for the first four notes of his fifth symphony; Tchaikovsky for the final moments of the 1812 Overture--and the list could go on; and that's just a few of the great composers whose names might strike a chord with some non-musicians. These compilation albums feature plenty of pieces by composers whose names don't get mentioned at all, but who were fortunate enough to find advertising posterity but writing something like the Canon in D (Pachelbel), Peer Gynt (Grieg) or The Light Brigade (von Suppe). Some composers, seeing the writing on the wall, concentrated on music guaranteed to be popular: the waltzing Strausses, march king John Philip Sousa.

As the album covers above demonstrate, though, many people view classical music as the auditory equivalent of brussels sprouts: very likely good for you, but extremely unpleasant to the palate. Getting even the tiniest hints of classical music in their ears meant dressing it up with a beat. Enter the jazz-classical arrangements of the big band era and, for my generation, disco classics:

That last expression of the popularization movement--a series of records with successive fragments of familiar works, all set to the monotonous downbeat of a disco drum--was the final stop in the evolution of classical music into soundbites. The next generation of popularizers starred British violinist Nigel Kennedy, who introduced a muscular, video-influenced version of Vivaldi's Four Seasons that, for all its excesses, leaves the music essentially untouched. Holding onto that same desire to perform entire works, rather than melodic snippets, but simultaneously pouring new wine into old skins were two gospel versions of Handel's Messiah:

All of these recordings, and their precursor, the pops concert, seek to make classical music tolerable to the majority of the population, who associate it with tuxedos, tails, large-breasted sopranos with wide vibratos, and an overwhelming sense of seriousness; but the classical world is hardly alone in its penchant for taking itself seriously. Think bebop. Think emo. Think any pop hit of the last decade that's in a minor key.

But seriously: to really appreciate classical music, one has to take the time to listen to it in a way that few people listen to music: attentively, presently, profoundly. You've got to let it into your brain, let it crowd out all the distractions, the thoughts and feelings and ideas that can turn this primarily instrumental music into nothing more than background noise. Attend to it, and the complex simplicity of it will blow you away. If it's really good, it can do that without a beat, without Fantasia style visuals, without a story line. But only if you'll give it a chance. Only if you'll let that unappetizing-looking spoonful into your aural tastebuds, and hold it there long enough to find out what it really tastes like.

Who knows? You might just become a sprout-lover.

Comments

Post a Comment