Turn It On

Yes, I do need you to use that microphone.

The presenter had just been handed a wireless microphone designed to fit around one of her ears. She held it in her hand for a moment, her expression bemused, then set it down on the table. Here we go again, I thought to myself. Sure enough, with a smile on her face, and using excellent projection technique, the presenter proclaimed, "I won' be needing thi'. You can all hear me, can' you? I've go' a good 'rong voi', don' I?"

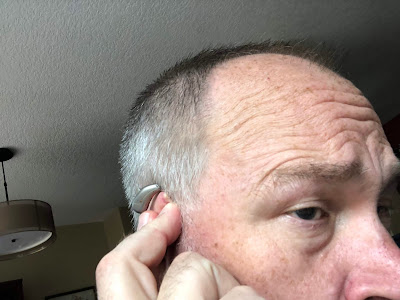

At least, that's what I heard. Her vowels came through loud and clear. Her sibilants, though--consonants pronounced with the tongue and teeth--were almost inaudible, even with my hearing aids turned up all the way. If she'd been looking right at me--if, rather than being in a large conference room, we were having a face-to-face conversation (hopefully not in a noisy coffee shop, which presents a whole other level of difficulty)--I probably would've been fine. But there were several dozen other people in attendance, and this being an Orff workshop, there was going to be plenty of movement, which means times when she'd be looking away from me, and I'd have to struggle to understand what she was saying.

So I sighed, and raised my hand. "Please use the microphone." And there I was again: the one guy in the room making the presenter uncomfortable by bringing up my disability.

I play that role in a variety of settings: during staff meetings at the school where I teach; at district-level trainings; at workshops hosted by my local Orff chapter; at national conferences of the American Orff Schulwerk Associations; and, most recently, at a level one World Music Drumming course. Again and again, I find myself having to advocate for myself and anyone else in the room too shy to admit that, like most musicians, I was exposed to too much cymbal-playing in my youth, and now I have a hard time with sibilants. My stepson, a recent high school graduate with a much more profound hearing issue, has encountered this situation on a daily basis, having to remind teachers (some of whom become hostile and skeptical of his need for amplification) to wear the microphone that connects directly to his hearing aids.

It's puzzling to me that so many people who teach and present are so reluctant to use vocal amplification technology. Speaking for myself, I was thrilled the first time my elementary music room was equipped with a PA system. From the first day I used it, I could tell a difference in my energy level: I stopped coming home exhausted. It's amazing how much energy goes into projecting one's voice over the myriad sounds of children making music and socializing with each other, especially when an essential part of the job is teaching songs by modeling. Add to this the fact that, as a man, I have to use falsetto if I expect my students to be able to match pitch, and no wonder my voice was fading to a whisper at the end of each day. Not so once the PA went in; and now, on top of having more energy at the end of the day, I was having less bouts of laryngitis spread over the school year.

I suppose it could come down to discomfort at the sound of one's own voice, something my ten years in the pulpit cured me of. Considering we are musicians and educators, it's a strange thing for us to get hung up over, especially when it could spell the difference between a student learning what we have to teach or becoming a behavior problem out of frustration.

The bottom line for me is that this is an equity issue. Whether you're teaching kindergartners, directing a choir, or presenting a workshop for a roomful of adults, chances are good that someone in that room has hearing impairment sufficient to render at least some of your unamplified lesson partly or completely incomprehensible. Simply consent to using the microphone, and you'll make the lesson significantly more enjoyable for that person.

To put it another way: you want all your students to learn. Knowing that your unamplified voice is creating an obstacle for some of them, why would you not use the sound system that's already in place or, if you haven't got one yet, demand that your administrator put one in immediately for the sake of your students?

And please, please, please don't make us ask for it. Of the four workshops I attended on the first day of last November's AOSA conference, I had to ask three of the presenters to use the microphone provided by the conference center. After that first day, I decided to just tough it out, channeling my frustration instead into the evaluations I wrote after each session. With my World Music Drumming course, it was another matter, as one of our presenters had to be reminded every time he stepped in front of us that without a microphone, even non-impaired participants were having a hard time hearing him. That continued for the entire week--and yes, I wrote about it on the evaluation.

But really, none of us should have to ask for a teacher or presenter to use technology that's already in place that will make it possible for every learner to hear, understand, and grow from what's being said or sung.

When I first experienced the Orff approach, one of the big draws for me was how overarchingly inclusive it was. Here was a way of teaching music that could reach every child. It behooves every one of us who practices this philosophy to seek out those who are being excluded for any reason--including the ones who can't understand what we're saying. These can be the simplest for us to include. All it takes is switching on a microphone.

Comments

Post a Comment