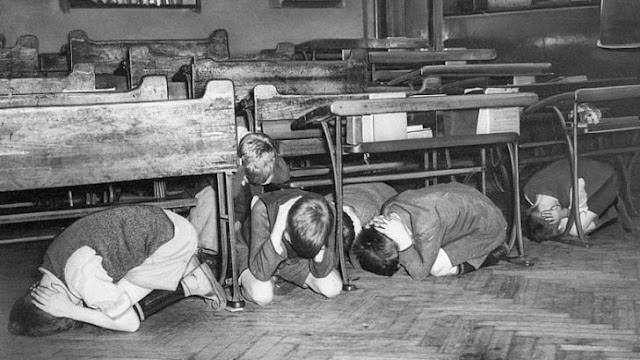

Duck and Cover for the 21st Century

Mid-twentieth century students practicing for the apocalypse.

No, I'm not that old. Duck and cover drills ended before I started school.

I did get a heavy dose of "Your Chance to Live" lessons, courtesy of the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (formerly the Office of Civil Defense), during my middle school years. This lessons took the forms of films and filmstrips about a variety of disasters: earthquakes, hurricanes, tornados, floods and, yes, nuclear war, the existence of which made the whole series necessary. Curiously, I don't remember any of those lessons taking place once I started high school, which leads me to wonder if having them be such a large part of public school was just an Idaho thing. (My family moved to Oregon the summer before my freshman year.)

Whatever the reason for exposing impressionable young students to so many ways we could all die, the result was probably not what the preparers of the curriculum intended. Being prepared didn't make me feel any safer. If anything, I felt more overwhelmed and helpless than if I'd never learned the stages of nuclear death. In a nuclear attack, I learned, death was inevitable for the vast majority of people within several miles of the explosion, whether it was from the unimaginable heat at the epicenter, being crushed by collapsing buildings or the shockwave, or toxic doses of radiation; and since it was the era of Mutual Assured Destruction, there were very few people fortunate enough to be living out of that range. And those lucky rural folk not slaughtered in the initial attack had only a limited reprieve from death: all the debris thrown up in the air would blot out the sun for years, while that which drifted back to earth would spread radiation to every corner of the planet.

No wonder the OCD/DCPA dropped its instruction to "1. Duck. 2. Cover." (and, in many an anti-war poster, "3. Kiss your ass goodbye.") "Your Chance to Live" was an inapt title for the curriculum, which could more accurately have been called "You're All Going to Die."

So let's jump ahead to the early 2000s, and my reentry to teaching. I trained for the profession during the Cold War, left it almost as soon as I started, and spent the late 1980s and all of the 1990s in the United Methodist ministry. The civil defense agencies I remembered from my own childhood had been absorbed into FEMA, and children were no longer being taught what to do if a hydrogen bomb took out the nearest city. Fire drills were, as they had been in my own childhood, still a frequent and inconvenient part of life for teachers and their students. The terrorist attacks of September 11 seemed not to have affected school life in any way.

Columbine, on the other hand, had introduced a new cause for alarm, as it introduced us to the concept of the active school shooter.

Active shooters had been a fact of life for decades. There had been incidents in workplaces and college campuses of a gunman systematically killing random victims. In Columbine, though, a new phenomenon asserted itself: shooters could be children who'd accessed their parents' guns, with or without their permission; or in places with ridiculously lax gun laws (which, if the NRA has its way, will include every jurisdiction in the United States), had simply gone out and bought them. These weren't just handguns or hunting rifles they were using, either: schools were being shot up with assault rifles with high-capacity magazines. These are military weapons, the sole purpose of which is to take human lives, and they are being used for precisely that.

That's why "duck and cover" is back--though it's really more like "hide in a corner with the lights off." In a lockdown drill, we teachers are instructed to lock our doors, turn off the lights, and have our entire classes huddle in a corner of the room that can't be seen through any windows. We're fortunate at my school in that, apart from the doors, there are no windows at all, so it's not hard finding a corner that's out of view. While the drill is being conducted, we expend a lot of effort quieting the children. Meanwhile, administrators roam the building, testing doors to make sure they're all locked. It's a great relief when the "all clear" is sounded.

We don't need civil defense films to tell us why these drills are so important. It's in the news. Since the beginning of this calendar year, school shootings have happened once a week. The conference I attended in November in Fort Worth, Texas, began with instructions of what to do if an active shooter entered the convention center. There have been mass shootings at a church in Texas, and a country music festival in Las Vegas. Acquiring a mass murder weapon and using it on a crowd of defenseless people has become a suicide fad.

And not all lockdowns are drills. In the sixteen years since I resumed my teaching career, I've been through at least four lockdowns that were initiated by word of a violent crime being committed in the area. One of them was an actual school shooting: Reynolds High School, June, 2014.

About 200 children a day pass through my music room. They are inquisitive, funny, awkward, goofy, distracted, charming, sweet, and, with almost no exceptions, innocent. The thought of any human being turning an assault rifle on them is so appalling to me that I find myself tearing up whenever I encounter news of a school shooting. I grieve the innocent lives lost, the permanent wounds it leaves in the survivors, the parents, the school, and the community. I'm furious that there is a powerful lobby that actively takes these tragedies as an opportunity to promote even laxer gun laws, and that the Republican party does their bidding without questioning even their most ridiculous policy proposals.

At the same time, for once, I feel hope. The surviving students of the Parkland massacre are calling bullshit on the Florida politicians, as well as President Trump, who have so easily slid into the ineffective platitudes with which Republicans traditionally try to spin away from the obvious implications of shootings to their reckless gun policies. And they're not stopping there: drawing on the lessons of the Women's March, they're organizing, putting together a march on Washington to demand action. Many of these young people will be of voting age, if not this fall, by 2020; and while 18-year-olds have been a historically apathetic demographic when it comes to the ballot box, there is nothing like feeling your life is at risk, and the party running the government doesn't care, to turn a nonvoter into an activist.

The original "duck and cover" gave birth to a generation of peace activists who, while they did not succeed in reversing the Cold War (it took the collapse of the Soviet Union to bring that about), did manage to get the United States to abandon the Vietnam War. Perhaps the lockdown generation can begin to reverse our national addiction to weapons of mass murder, starting with restrictions on their sale and confiscating them from the minors and people with records who should never have been permitted to buy them in the first place.

It'll be hard work. The NRA is powerful, and the Republican party is full of cowards unwilling to stand up against it. But there's nothing like the fearless righteousness of a teenager to cut through the excuses and nuances of a debate that we've permitted to become far more complex than it needs to be. Less guns means less death, and if anyone has the right to insist on that truth, it's the young survivor of a school shooting.

Hard work, yes. But it sure beats hiding in a dark corner, waiting for the killer to break through the door.

Comments

Post a Comment