Studying While Rome Burns

United Methodists would rather study than decide.

I begin with confession.

As I've written before, I was not temperamentally well suited for the ministry. The most successful pastors are extraverts who can work crowded rooms, skillfully making every interaction feel like an intimate one-on-one. There are exceptions to this rule, introverts who teach themselves to be more competent greeters, but really shine during in-depth conversations where their excellent listening abilities make for more profound connections. Personally, I much prefer the latter qualities in a pastor, but I completely understand the draw of the warm, electric, extraverted crowd-pleaser.

I'm an introvert. There's no getting around it: I don't do well with meet-and-greet occasions. Interpersonally, I'm at my best when I've got the time and space to talk deeply with just one other person, and during my ministerial career, I made that kind of connection a number of times.

To do that, though, I had to make cold calls. At the beginning, I did it by dropping in, driving to someone's house, ringing the bell, and having a chat. This wasn't easy for me; getting myself out the door, into my car, and across town to whomever I'd decided to visit that day took some heavy emotional lifting, and once I got to that house, especially if it was someone I hadn't visited before, This was not a rational fear: almost all my home visits went well, and the people I visited became some of my strongest advocates at church meetings. Even knowing this, though, there was never a time when I didn't hope I'd find nobody home, be able to leave my card (I always got credit for trying). And that was Illinois and England, where people didn't mind having spontaneous drop-ins from their pastors. In Oregon, people expected a phone call and an appointment before I made home visits, and as hard as it was for me to knock on their doors, that was nothing next to picking up the phone, a device that has always given me deep anxiety. I'd rather spend a half hour driving to someone's house, finding (thank God!) they're not home, and leaving my card than making a one-minute call to tell them I'm coming.

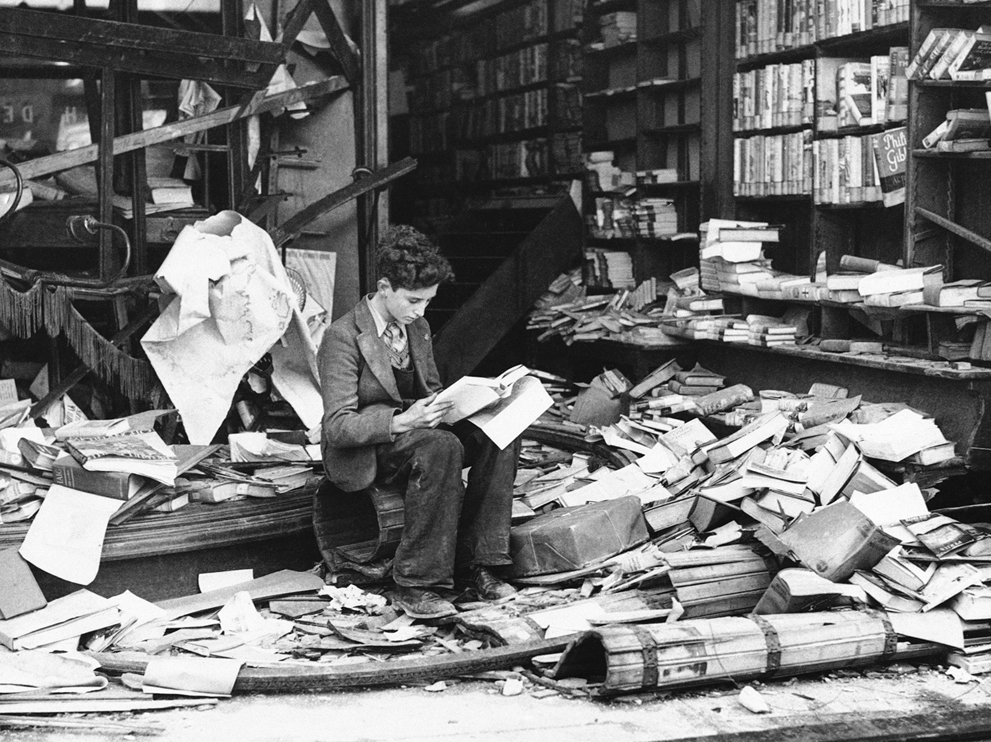

Where I really wanted to be on all those difficult visiting days was in my study. Pastors are expected to spend a significant part of their work weeks in study. They read commentaries and books of theology, go over the scripture lessons they'll be preaching on the following Sunday with fine tooth exegetical combs, consult concordances and lexicons to parse the meaning of troublesome words, dig through their files in search of powerful illustrations, write, edit, rewrite, until they've got a 15-20 minute meditation that (they hope) will be both relevant and captivating. Once it's in the can, they may spend additional time practicing, talking themselves through passages and transitions that feel awkward, working on delivery, making absolutely certain that what comes out Sunday morning is the best piece of religious performance art they can pull off.

For an introvert, especially a scholarly, creative introvert who enjoys performing, this is the best part of the job. The danger is that it can easily become the only part of the job. "What's this? 11:00? Where did the morning go? I guess I'll have to wait for the afternoon to do my visiting--don't want to interrupt anybody's lunch, after all. Say, I'll bet that book on Black liberation theology would give me some insights into next week's Peace with Justice Sunday sermon. Aw, nuts, now it's 4:00. If I go out now, people will be starting dinner. Well, there goes the day..."

Speaking for myself, I found that, as the years went by and my preaching muscles grew ever more toned, I really didn't need as much time in the study to be able to deliver an inspirational sermon. Toward the end, in fact, I was improvising in the pulpit. Oh, I'd read the appointed texts in advance, get my subconscious working on them, maybe even generate a title--which I'd most likely change when I stepped up to preach, because that morning I'd had a sudden insight, and was ready to work it out right in front of the congregation. And the people responded to both the spontaneity of the message and the smoothness of the delivery, often asking me for a copy of the sermon--something I couldn't provide, as it had happened in the moment.

And still, I found reasons to spend most of my week in the study. Which is why I'm not a minister anymore. You see, I knew that what I was doing, however important the final product (there are parts of the United States where pastors are simply referred to as "Preacher"), what really mattered was the work of building relationships, both in those large gatherings and in the intimate home visits; and I sucked at the former, and couldn't motivate myself to do the latter. So in January 2000, the United Methodist Church finally, in as gentle and humane a way as it could, eased me out of ministry. I was angry for a few months, tried to get back in after 9/11, but ultimately found that teaching music was where I really belonged. Since around 2005, I haven't looked back once.

That last year was hard, though, painful, awkward, frustrating for all concerned. Weirdly, though, even as I was being a lousy United Methodist minister, I was doing it in a way that was quintessentially Methodist.

This is the point in a sermon where suddenly the illustration is revealed to be a parable, and through a skillful pivot, the personal transitions to the political. I'll do it with two words: General Conference.

For the non-Methodists out there, General Conference (or "GC," as we insiders like to call it) is a quadrennial gathering of representatives throughout the worldwide denomination known as the United Methodist Church. This is the only governing body within the church that can make policy decisions. Its primary function is to amend the Book of Discipline, the rule book that spells out every aspect of church administration. Most of the GC's decisions are uncontroversial, even when they have social justice implications (one section of the Discipline is given over to the church's official platform, including statements on civil rights, addiction, labor, and any other issue that catches the fancy of a majority of delegates). The exception to this is anything having to do with human sexuality in general, and particularly anything applicable to the LGBTQ community.

For 44 years, United Methodists have been engaged in a theological civil war over what used to be called gay rights. It started in 1972 with the insertion into the Discipline of the "incompatibility clause," which declared that homosexuality is "incompatible with Christian teaching," and therefore rendered any candidate for ordination ineligible for the pastoral office. Every GC since 1972 has seen efforts to delete or amend this clause. These efforts have been rebuffed by a growing majority of delegates from the South and Midwest, augmented in recent years by the tremendous growth of United Methodism in Africa, particularly in countries in which homosexuality is viewed as a crime.

As the two sides of the controversy grow more strident, and as the views of Americans become more open not just to ordaining LGBTQ individuals, but allowing them to marry, and encouraging them to do it in a church, blessed by a pastor, the divide within General Conference has deepened, the floor debates have become more passionate, protests have escalated, and presiding Bishops have called in security officers to remove demonstrators from the conference floor. There's no sign that the hardened hearts of the conservatives will, at any point, soften to permit a true revision of the Discipline; and with their eyes on the prize of true equality, the LGBTQ-friendly forces in the church are not about to back down. When the 2016 General Conference convened in Portland, Oregon two weeks ago, the buzz around the denomination was that this was it: the church was finally going to dispense with the fiction of being United Methodists, and formally begin the process of schism.

It stayed that way for the first week. The legislative committee responsible for vetting proposals on human sexuality could not advance a single action request to the plenary session, as it was blocked repeatedly by conservative committee members. A process was worked out to go around this bloc, to enable a floor debate that would, almost certainly, when it came to the inevitable rejection of whatever proposal was being debated, result in a walk-out by a significant number of delegates, loss of a quorum, and a whimpering end to United Methodism as the conference dissolved in disarray.

That's when the Council of Bishops stepped in. These elected "shepherds of the church" see themselves as called to hold the greater flock together, preaching in soothing generalities about harmony and unity, pausing emotional debates to engage in prayer, and always seeking a middle way that can hold the denomination together. That's what they did last week, putting forward a proposal that all votes on human sexuality be deferred until the Bishops could assemble a blue ribbon panel to study the issues, then make a recommendation about calling a special session of General Conference.

Yes, that's right: rather than dig into the deep divide in the church, the Bishops called for a study. And the conference agreed.

If you're a lifelong Methodist, you need to take a moment to stop your eyes from rolling so hard they might pop out of your head. Faced with controversy, Methodism's go-to solution is studying the issue. Millions are spent assembling panels of experts, consulting across the denomination, compiling findings, distilling them into study guides, distributing them to congregations, hearing back from those congregations and, years after the initial proposal was deferred so it could be studied, finding that people are still pretty much exactly where they were before the study. We went through this is 1992. Two years later, the congregational materials arrived in my church mail box, and I led some study sessions that changed no minds. At General Conferences in 1996, 2000, 2004, and every meeting since, it's as if the study never happened.

The church I pastored in 1994--the Estacada United Methodist Church--had actually done its own study several years earlier, and proclaimed itself the first Reconciling Congregation in the Oregon-Idaho Annual Conference. It wasn't the local conference-generated study materials that really made the difference in Estacada, though: it was having a gay member who had grown up in the church. Knowing him as a human being, seeing his struggles, understanding how unfair the denomination's condemnation of his identity was, they came to the conclusion the church as a whole has been avoiding since 1972: it's the human being who matters, not his or her orientation. If God wants this person to be a pastor, or that couple to get married, the role of the church is celebration, not condemnation.

No amount of studying is going to make that connection. What will is entering into dialogue with people who have different orientations, getting to know them deeply, intimately, as fellow human beings and children of God, and knowing, profoundly, that they are as deserving of all the ordinances of the church as anyone who just happened to be born straight and cisgendered.

I don't hold out a lot of hope for such connections happening in the places that need them if the church is going to stay United. So despite having very Methodistically delayed the final reckoning with yet another study, I expect this to be the last General Conference of the United Methodist Church. When the next session happens, whether it's a special called conference or, should the study (as typically happens with Methodist studies) take longer than anticipated, the regularly scheduled quadrennial General Conference, its sole order of business will be the orderly dissolution of the denomination.

I will be sad to see it go. Even though United Methodism ceased to be me spiritual home early in this century, it is the church that formed me and, for decades, guided my path. In United Methodism, I had profound encounters with sincere Christians who were dedicated to making their corner of the world a far better place. I heard moving testimonies, was ministered to compassionately, and when I could no longer carry out my pastoral vocation, eased out of it gently and with sincere concern. But I have to say that all of this goodness came not from the denomination, but from individual Methodists living out their own callings; and they are the ones who will carry on the thoughtful, purposeful work of the church, crafting a new reality that welcomes people of all genders and orientations in life-affirming ways.

They just won't be able to call themselves United Methodists anymore.

Comments

Post a Comment