Still Racist, After All These Years

Is it just me, or do you see the similarity, too?

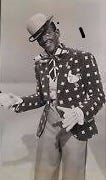

Bing Crosby in blackface.

I rubbed my eyes, tried to wish it away, but there it was: midway through Holiday Inn, the classic musical that introduced "White Christmas" to the world, there was a blackface number. It wasn't just Bing doing the bit, either: there was a whole chorus of white people, all done up the same way, gathering around as he sang a ballad of "Abraham" (Lincoln, that is) who had "set the darkie free."

The year was 1983, and I had begun a decades-long quest to see every classic musical I could. This one happened to be on TV a few hours before I boarded a train from Champaign, Illinois that would take me home for Christmas break. I was charmed by the high concept of the film--a hotel open only on holidays--and the chance to see Crosby paired with Fred Astaire (and yes, that's him, not Der Bingle, in the picture). But then came the Lincoln's Birthday number, and I was simultaneously stunned and revolted by what I saw.

To put this in my own personal context: I was a white boy who grew up in white culture. I did not meet an African-American until college, and there were few even there. Even at the University of Illinois, where I went to grad school, the music department was notably lacking in diversity. And yet, I knew what I was seeing and hearing was wrong.

Historically speaking, 1942 was a different time from 1983. World War II and the civil rights era rendered the culture of the minstrel show (which I'll get into shortly) obsolete, though many popular characters would carry on its traditions and iconography. I was not much of a partier in college or grad school, but I did attend costume parties, and don't recall ever seeing any of my classmates darkening their complexion for those occasions. This was also the era, though, that produced the blackface yearbook photo that may yet bring down Virginia governor Ralph Northam. And fifteen years later, I was assistant dean at a church camp that nearly came apart over an incident in which, for an evening entertainment, a white counselor put on dark make up and pretended to be a gospel preacher, leading several black campers to call home, and the dean and me to have an extremely uncomfortable time explaining to their parents how this had happened.

Setting aside what Ralph Northam did or did not do in the early 1980s, and what a camp counselor did in the late 1990s, look at the picture at the top of this blog. It comes from GoNoodle, a web resource for parents and educators that engages children in learning and exercise through videos, many of them available on YouTube. The character in this picture is called Maximo, and he is the star of a number of dance videos. I saw one of them used to teach the Macarena to children several months ago, and my first thought seeing the character was that he's straight out of a minstrel show. Investigating a little more deeply, I see that he's been given a mustache and a Mario-style Italian accent (trafficking in yet another stereotype, but let's not go there yet). Still, the image--dark skin (blue in this case) emphasizing white eyes and teeth, top hat, suit--rings alarm bells for anyone who's seen images or film from a minstrel show.

Minstrel shows were one of the oddest manifestations of the melting pot of American culture. Starting in the early 1800s, these shows featured white performers in blackface, performing caricatures of African-descended slaves in skits and musical numbers. The humor was broad, the portrayals devastatingly racist. At the same time, the songs and dances performed popularized the musical culture slaves had crafted by merging African forms and rhythms with American hymns and popular songs, creating the first glimmers of what would evolve into Blues, jazz, gospel, and ultimately, rock. Adding to the perversity of the genre was the cluelessness of white minstrel performers regarding the true meaning of the songs they sang, many of which ridiculed white people using coded language.

Following the Civil War, former slaves were now free to take the stage and perform in their own right--except that white audiences preferred the exaggerated features of blackface to actual black faces. So these performers acquired the same makeup as their white colleagues, heightening their features into caricatures of themselves, performing the same material but now with the added dimension of knowing they were satirizing their own audiences who still remained ignorant of hidden textual meanings. The practice continued, as can be seen in Holiday Inn, right up to the 1940s. The Jazz Singer, the first successful sound movie, tells the story of a white singer who must wear blackface to perform the songs he loves. Even Stormy Weather, a ground-breaking musical with an all-African-American cast, features a blackface vaudeville number, a brilliant demonstration of comic timing marred by the burnt cork on the performers faces.

The point I'm making is that there is no way to divorce American popular culture from its genocidal roots. American popular music would not exist without the minstrel show. It's the way in which the millions who made the middle passage finally have the last laugh on their genocidal kidnappers: their music, their culture, rules the world now. Our musical voice will always be tinged with the grief and suffering of the countless millions torn from their homelands, separated from their families, robbed for centuries of the simple rights to marriage, raising one's own children, and enjoying any of the fruits of their labors.

America does not want to know this. We don't want to know that our culture came from these sources, anymore than we want to know that the land we live on was stolen from an indigenous population who died that we might prosper. We want to believe we're the land of the free and the home of the brave, that justice and equity have always reigned throughout our land. So we tamp down the memories of how we got here, pray that nobody ever sees that yearbook photo we really should've said no to, reads that editorial in the campus newspaper that should never have been printed, or asks what really went on at that Michael Jackson dance-off.

But these things happened, they weren't just isolated incidents, and they're still affecting popular culture. Watching the GoNoodle video of Maximo doing the Macarena, I wonder how many black kids feel something wrong in the way that character looks and moves, something all-too-familiar about his face, his hands, his outfit. I have come to wonder the same thing about some of the storybook characters I most loved as a child: comparing the Cat in the Hat to the Interlocutor, a popular minstrel/vaudeville character, it's impossible not to see the similarity. So, too, with many a Disney or Warner Brothers cartoon. I had no idea, watching these shorts as a child, that many of the mannerisms and jokes I found hilarious had their genesis in white people made up to look like black people, lampooning their mannerisms and speech patterns.

In Virginia, the statehouse is in turmoil over cascading revelations of regrettable racist incidents buried in the histories of many white politicians. I suspect that could be the case for a sizable percentage of people who grew up, as idea, in the 1960s and 1970s, aware that there had been a paradigm shift with respect to people of color, but not quite clear yet on how we ought to change our own behavior as a result. There are, I think, a lot more Ralph Northams out there, hoping nobody finds their yearbooks.

I don't think the solution is sweeping them all out of office. Minstrelsy, blackface, vaudeville, and the songs and dances that were integral to their commercial success gave birth to the nation we are now. Some of them may even have been performed not to lampoon, but to honor, the culture they portrayed. Al Jolson sang "Mammy"in blackface as an homage to the people who created the music he loved. The blackface number from Holiday Inn, as paternalistically painful as it is, seeks to honor Abe Lincoln the liberator. No, that doesn't excuse any of these performers for doing what they did. Nor does the good Ralph Northam has done, and will do, as a politician who is still backed by a large majority of his African-American constituents give him a pass on the racist incidents of his youth.

It does, however, create an opportunity for truth and reconciliation. African-Americans have been living with the descendants of their enslavers for more than 150 years now. More than that, they've been living with the people who promulgated Jim Crow, who had to be forced to give them every right they extracted through the civil rights eras, and who now are again trying to rob them of their voting rights. They've been living in peace with these people who've treated them so abominably. And they deserve an apology.

America does not like to apologize. In my lifetime, every apology that came from a president--whether it was for massacring Native Americans, interning Japanese-Americans, or toppling democratically elected leftists to replace them with fascist puppets--has been met with jeers by large numbers of Americans who'd rather believe their country can do no wrong.

The truth is that we've done a lot of wrong, and it's time we admitted it and apologized for it. I think if Ralph Northam and the other southern politicians with racist skeletons in their closets would come clean about it, admitting their mistakes, repenting of them, and transforming them into the impetus for a new era of expanded rights, reparations, and the promotion of diversity, they'd find the people most deserving of those apologies quite receptive to them. They would also want to know what Governor Northam is going to do for them and their community now and in the future.

As for GoNoodle: how I wish they'd make Maximo go away. The Macarena isn't even a kid-appropriate song, let alone an excuse for exposing new generations to the cultural embarrassment that is the minstrel show.

And don't even get me started on how offensive his accent must be to Italian-Americans.

Maximo was an excellent character that my students loved. However, people like you (social justice warriors) have to put ideas out in the public and on media to destroy something that was pure and innocent. I grew up watching Bing Crosby movies too and I never saw Maximo as a blackface minstrel character. I saw him as a calming, funny character that helped my students wind down from an active day. He wasn't a racist character and neither is GoNoodle for including him in their repertoire.

ReplyDeleteSimply being unaware of this history doesn't make it "pure" or "innocent". These videos are remarkably offensive representations of various cultures, and calling people "social justice warriors" doesn't make your statements any less appalling as a self-proclaimed educator. Educate yourself. 🤦♂️

Delete