Wisdom to Know the Difference

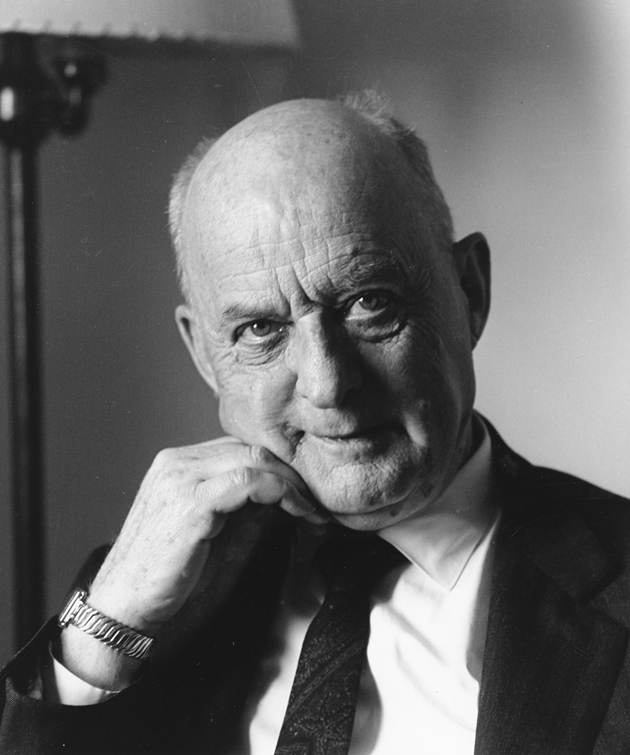

Reinhold Niebuhr

He looks so benign. Who could even guess this avuncular baldy was mid-century America's answer to Machiavelli?

Reinhold Niebuhr's career was the ecclesial and academic equivalent of Barack Obama's rise to the Presidency. Niebuhr was an ordained minister in the Evangelical Church, a mainline Protestant denomination (this was in the days before "Evangelical" became synonymous with "reactionary") of primarily German immigrants. Niebuhr's first and, it turned out, only parish was in Detroit. It was small when he arrived, large by the time he left, but that probably had as much to do with demographic shifts as anything else: Detroit was growing by leaps and bounds as the auto industry matured. If his memoir of those years, Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic, makes clear, he was frequently neglectful of the more mundane aspects of the pastorate, preferring instead to nurture a developing career as an activist and theologically oriented pundit, which he ultimately spun into a position at Union Theological Seminary. "Professor of Practical Theology" identifies his subsequent work beautifully.

Niebuhr professes in his early writings to be an idealist, a pacifist who modeled his actions on the life of Jesus. As such, he found much to appreciate about the work of Gandhi. As his thirteen year pastorate drew to a close, though, he experienced a shift to a branch of theology called neo-orthodoxy, and from there to the school of thought he created: political realism (sometimes referred to as Christian realism). In his maturing theology, Niebuhr came to believe that ideals were fine as guiding principles, but that no decisions made in the political realm could be purely idealistic. Rather, the challenge was to sift through all the evidence and arrive at the most moral--conversely, the least immoral--plan of action. Many of the positions he endorsed are debatable, but there is no arguing with the central truth of his approach: political decisions must be constantly scrutinized to be sure that the compromises essential to politics do not tip into immorality.

I first encounter Niebuhr in a seminary course on moral theology. Later I came back to take an entire seminar on his writings, not out of choice, but simply because all the courses I was really interested in were full by the time I arrived at registration. As it turned out, that seminar turned my own thought process upside down. I found myself arguing with Niebuhr's conclusions, but unable to fault his methodology. Idealism is a fine thing for an individual to practice, Niebuhr wrote, but once that individual joins with other idealists, conflicts are inevitable. If their community is to survive, there will have to be compromises. If that community is to be part of a larger collective--a city, a state, a kingdom, a country--compromise must be an essential part of the unification, and the only way to avoid tyranny (the imposition of one set of ideals on an entire group of people) is for the collective to be governed democratically. And as much as the concept of democracy may itself by an ideal, its very nature--giving voice to all the disparate views within a collective, but conceding ultimate authority to the will of the majority--is a combination of compromise and tolerance. The hardline idealists must concede points to the greater majority, who must tolerate the ongoing presence of hardliners. Disrupting this balance leads to political gridlock and, ultimately, civil war.

I remember sitting with Niebuhr's 1932 masterpiece, Moral Man and Immoral Society, and wanting to throw it against the wall, because as much as I didn't want it to be true, I knew it was. The book was more an extended essay than a scholarly work--Niebuhr rarely cites references--but his understanding of history is inescapable: whatever heights individuals may aspire to, the tragedy of the commons ultimately brings them down. I was 29 when this finally sank in. Niebuhr later summarized his belief in democracy in this aphorism: "Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible; but man's inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary." (The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, 1944).

Which brings me to the present. Politics, I have come to realize, is the realm of necessary compromise. Barack Obama campaigned as an idealist--though many of his avowed ideals were those of a deal-maker, one who hoped to bring the poles of American opinion together in the middle--but had to govern, from his first day as President, as a realist. To save the economy, Obama had to bless deals with banks and corporations that made both socialists and libertarians furious. To bring long-needed reforms to public health, he had to make deals with insurance companies and conservative legislators that preserved America's unenviable status as having the most complicated health industry in the world. The clear practical gains of these moves, along with significant progress on civil rights, appeased many on the left, but infuriated the idealists on the right, resulting in the least-productive Congress in American history. To quote Niebuhr again (though I'm not sure where this reference originates): "The whole art of politics is directing rationally the irrationalities of man."

It's cliched, but true, that Washington is where ideals go to die. Jimmy Carter's failures at governing idealistically resulted in twelve years of Republican ideals running the country, moderated by eight years of Clintonian realism. There was much about the Clinton era that frustrated social liberals like me--the dismantling of welfare, the lack of progress on gay rights, the utter failure of health reform, and don't get me started on the loose zipper morality of Bill Clinton, not to mention the glib lawyerisms he used to evade responsibility--but by the end of that time, the country was heading in a far better direction. A Gore administration could have cemented many of these changes. But the idealists on the left wouldn't have it. Instead, they threw their support behind the third party candidacy of Ralph Nader, drawing just enough votes away from Gore to put another Bush in office.

I voted my head, and not my heart, in that election, and the results confirmed that decision. I'll be voting in the same way this year, putting realism ahead of idealism. I want everything Bernie Sanders promises, but I don't believe he can deliver any of it from the Oval Office. The entirety of the Sanders agenda is dependent on the cooperation of Congress, and one does not simply pass idealist legislation through the Senate, let alone the House. Fence-straddling, eggshell-walking, compromise, diplomacy, deal-making--none of these come easily to an idealist. A Clinton, on the other hand--which is to say, a political realist--can cut half a dozen deals while doing the New York Times crossword (and I'll cut off the joke there).

And that, my friends, is the Niebuhrian reason I'll be voting for Hillary Clinton: I'm compromising my ideals in favor of real progress. That doesn't mean I want those ideals to go away. Niebuhr honored and respected the idealists of his world--Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr.--for establishing a moral pole toward which the politicians could move. Washington of 2016 has idealists, too, thinkers whose intellectual purity should guide our pragmatic future President as she works those necessary compromises. Bernie Sanders won't be President, but that doesn't mean he should stop railing against corporate influence on Washington. Elizabeth Warren, too, can help steer voter opinion (and, with it, Congress) toward policies that favor ordinary people over millionaires.

One last bit of Niebuhrian wisdom before I close out this 401st blog post: "The tragedy of man is that he can conceive self perfection but cannot achieve it." Or, to put it more comfortingly in words for which he is best known: "Lord, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference."

Reinhold Niebuhr's career was the ecclesial and academic equivalent of Barack Obama's rise to the Presidency. Niebuhr was an ordained minister in the Evangelical Church, a mainline Protestant denomination (this was in the days before "Evangelical" became synonymous with "reactionary") of primarily German immigrants. Niebuhr's first and, it turned out, only parish was in Detroit. It was small when he arrived, large by the time he left, but that probably had as much to do with demographic shifts as anything else: Detroit was growing by leaps and bounds as the auto industry matured. If his memoir of those years, Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic, makes clear, he was frequently neglectful of the more mundane aspects of the pastorate, preferring instead to nurture a developing career as an activist and theologically oriented pundit, which he ultimately spun into a position at Union Theological Seminary. "Professor of Practical Theology" identifies his subsequent work beautifully.

Niebuhr professes in his early writings to be an idealist, a pacifist who modeled his actions on the life of Jesus. As such, he found much to appreciate about the work of Gandhi. As his thirteen year pastorate drew to a close, though, he experienced a shift to a branch of theology called neo-orthodoxy, and from there to the school of thought he created: political realism (sometimes referred to as Christian realism). In his maturing theology, Niebuhr came to believe that ideals were fine as guiding principles, but that no decisions made in the political realm could be purely idealistic. Rather, the challenge was to sift through all the evidence and arrive at the most moral--conversely, the least immoral--plan of action. Many of the positions he endorsed are debatable, but there is no arguing with the central truth of his approach: political decisions must be constantly scrutinized to be sure that the compromises essential to politics do not tip into immorality.

I first encounter Niebuhr in a seminary course on moral theology. Later I came back to take an entire seminar on his writings, not out of choice, but simply because all the courses I was really interested in were full by the time I arrived at registration. As it turned out, that seminar turned my own thought process upside down. I found myself arguing with Niebuhr's conclusions, but unable to fault his methodology. Idealism is a fine thing for an individual to practice, Niebuhr wrote, but once that individual joins with other idealists, conflicts are inevitable. If their community is to survive, there will have to be compromises. If that community is to be part of a larger collective--a city, a state, a kingdom, a country--compromise must be an essential part of the unification, and the only way to avoid tyranny (the imposition of one set of ideals on an entire group of people) is for the collective to be governed democratically. And as much as the concept of democracy may itself by an ideal, its very nature--giving voice to all the disparate views within a collective, but conceding ultimate authority to the will of the majority--is a combination of compromise and tolerance. The hardline idealists must concede points to the greater majority, who must tolerate the ongoing presence of hardliners. Disrupting this balance leads to political gridlock and, ultimately, civil war.

I remember sitting with Niebuhr's 1932 masterpiece, Moral Man and Immoral Society, and wanting to throw it against the wall, because as much as I didn't want it to be true, I knew it was. The book was more an extended essay than a scholarly work--Niebuhr rarely cites references--but his understanding of history is inescapable: whatever heights individuals may aspire to, the tragedy of the commons ultimately brings them down. I was 29 when this finally sank in. Niebuhr later summarized his belief in democracy in this aphorism: "Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible; but man's inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary." (The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, 1944).

Which brings me to the present. Politics, I have come to realize, is the realm of necessary compromise. Barack Obama campaigned as an idealist--though many of his avowed ideals were those of a deal-maker, one who hoped to bring the poles of American opinion together in the middle--but had to govern, from his first day as President, as a realist. To save the economy, Obama had to bless deals with banks and corporations that made both socialists and libertarians furious. To bring long-needed reforms to public health, he had to make deals with insurance companies and conservative legislators that preserved America's unenviable status as having the most complicated health industry in the world. The clear practical gains of these moves, along with significant progress on civil rights, appeased many on the left, but infuriated the idealists on the right, resulting in the least-productive Congress in American history. To quote Niebuhr again (though I'm not sure where this reference originates): "The whole art of politics is directing rationally the irrationalities of man."

It's cliched, but true, that Washington is where ideals go to die. Jimmy Carter's failures at governing idealistically resulted in twelve years of Republican ideals running the country, moderated by eight years of Clintonian realism. There was much about the Clinton era that frustrated social liberals like me--the dismantling of welfare, the lack of progress on gay rights, the utter failure of health reform, and don't get me started on the loose zipper morality of Bill Clinton, not to mention the glib lawyerisms he used to evade responsibility--but by the end of that time, the country was heading in a far better direction. A Gore administration could have cemented many of these changes. But the idealists on the left wouldn't have it. Instead, they threw their support behind the third party candidacy of Ralph Nader, drawing just enough votes away from Gore to put another Bush in office.

I voted my head, and not my heart, in that election, and the results confirmed that decision. I'll be voting in the same way this year, putting realism ahead of idealism. I want everything Bernie Sanders promises, but I don't believe he can deliver any of it from the Oval Office. The entirety of the Sanders agenda is dependent on the cooperation of Congress, and one does not simply pass idealist legislation through the Senate, let alone the House. Fence-straddling, eggshell-walking, compromise, diplomacy, deal-making--none of these come easily to an idealist. A Clinton, on the other hand--which is to say, a political realist--can cut half a dozen deals while doing the New York Times crossword (and I'll cut off the joke there).

And that, my friends, is the Niebuhrian reason I'll be voting for Hillary Clinton: I'm compromising my ideals in favor of real progress. That doesn't mean I want those ideals to go away. Niebuhr honored and respected the idealists of his world--Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr.--for establishing a moral pole toward which the politicians could move. Washington of 2016 has idealists, too, thinkers whose intellectual purity should guide our pragmatic future President as she works those necessary compromises. Bernie Sanders won't be President, but that doesn't mean he should stop railing against corporate influence on Washington. Elizabeth Warren, too, can help steer voter opinion (and, with it, Congress) toward policies that favor ordinary people over millionaires.

One last bit of Niebuhrian wisdom before I close out this 401st blog post: "The tragedy of man is that he can conceive self perfection but cannot achieve it." Or, to put it more comfortingly in words for which he is best known: "Lord, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference."

Comments

Post a Comment