Minority Envy

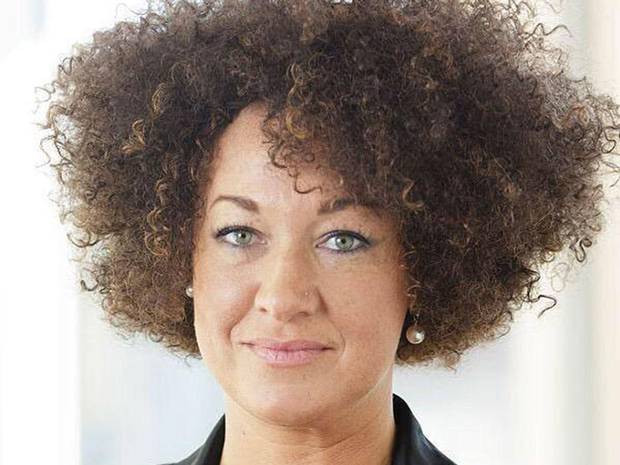

Rachel Dolezal

In almost every category Americans use to discriminate, I come out on top.

I'm white. Very very white. I don't tan; I freckle.

I'm a melange of European blood lines--French, German, Swedish, Scottish--that plant me firmly in the Anglo-Saxon camp.

I'm solidly Protestant: Baptist-Methodist, to be exact.

I'm university educated, with a Bachelors and two Masters degrees, plus enough post-graduate credits to put me on the top step of my district's pay scale.

I'm neither too tall nor too short, and have an average weight for a man of my age and height.

And last, but certainly not least, I have a Y chromosome.

With all these status points in my favor, one would think I would've lived a charmed life up to this point: privilege, wealth, career, easy credit, immunity from traffic tickets, and all the other benefits, both tangible and intangible, typically enjoyed by male WASPs. And in fact, I almost certainly have been given the benefit of the doubt by traffic cops far more often than I deserved. When it comes to employment, though, I've frequently found myself passed over for someone younger, more bilingual, and, frequently, female--all thanks to being a middle-aged over-educated man whose college Spanish is so rusty he needs to have the most basic sentences repeated to him S-L-O-W-L-Y if he's to parse them for meaning--in my chosen profession of elementary general music education.

But that's a side grumble. I know that my white complexion and graying hair have accorded me far more respect than I have any right to on many occasions (ahem, traffic steps), and that this is utterly unfair to the majority of Americans who are either female, non-white, or both.

The irony of it is that at least as far back as the fourth grade, I had minority envy.

It started with a YA novel I read about a blind boy and his seeing-eye dog. Wow, I thought, this kid is really different, and he has a wonderful relationship with this very special dog, and everyone can see how different he is. I liked the thought so much that I fancied myself vision-impaired--and in fact, if it weren't for the thick-lensed glasses I wore, my extreme near-sightedness would've rendered me disabled. But I lived in the twentieth century, benefitting first from glasses, then contact lenses and finally, a year and a half ago, LASIK; so thanks to technology, I could never honestly call myself blind.

All right, then, maybe I could belong to a religious minority. Learning about the Holocaust, I imagined what it must have been like to be a persecuted Jew, clinging steadfastly to my faith even as it singled me out for genocide. Or what if I had different-colored skin? What if I was Black, Asian, Native American, living in a culture that persecuted persons of color? I picked up Black Like Me and devoured it, fascinated by the idea of changing my skin and experiencing life under persecution.

And so on and so on and so on. My favorite science fiction novels were about aliens adjusting to life among humans or vice versa. I loved the theme of the stranger in a strange land, and coveted it for myself. Of course, from 1969-1975, I lived that life, and simply wasn't aware of it: being a Methodist in southern Idaho, a thoroughly Mormon land, put me in a very small minority. But I digress: I longed to know what life was like on the other side of the prejudice barrier.

This led me, in seminary and for years afterward, to dig deeply into African-American spirituality and gospel music, including my five-year stint as a gospel pianist in a small Black church in Northeast Portland. It's also informed my work with a thoroughly diverse student population at Margaret Scott Elementary School. I work hard at appreciating all the cultures represented in my classroom, trying to project myself into their experience, imagining what it's like to be Samoan, Vietnamese, Ethiopian, Mexican, Romanian, and attending an American school staffed almost entirely by white people.

But that's another digression. What occasioned this post is the sudden ubiquity of a racially white woman who has been not just passing as African-American, but as a leader in the Black community of Spokane, Washington. Why would she do such thing? How has she gotten away with it so long? How can anyone believe anything she says? There are plenty of questions people are asking about Rachel Dolezal, and with good reason. It's an amazing story, utterly unprecedented.

I don't know that I can shed any more light on it than the plethora of other bloggers and pundits who've held forth in the last week, but on a purely personal note, I can say this: my first reaction on reading what she'd done was, "Cool."

I say it because I had an opportunity to do, on a much smaller scale, what she did as head of the NAACP in Spokane. Toward the end of my five years playing at the Church of the Good Shepherd, Rev. Willie Smith was wondering, during one of our pre-worship bull sessions, who would take his place. He was in his late 70s, and as vigorous as he was, he knew he would eventually have to hand the reins of this church over to someone else. The way he was talking made me think he was fishing for me to offer myself. I was, after all, an elder of the United Methodist Church, officially appointed to the music ministry of Good Shepherd, and I was, at that time, preaching monthly, as well as filling in for Willie whenever he went on vacation. My spirituality was still nominally Christian. But the last thing I wanted was to take on all the responsibilities of pastoring a struggling congregation: I was just starting to get established again in music education, my most pressing concern was single parenting my children, and theologically, I was steadily moving toward unitarianism and, from there, to the post-Christian panentheist agnosticism I currently practice. I had also never been the kind of pastor who could inspire great things from a small congregation. They might say "Amen!" to my sermons every Sunday, but the doors would not stay open long with me as their leader. They needed someone far more inspirational, someone who could sincerely proclaim the Gospel as they understood it, and that someone was definitely not me. So I never took the bait. And when it came time for Willie Smith to, in failing health, step down just two years before his death, the pastoral leadership of Church of the Good Shepherd passed to Dapo Shobomehin, a community organizer and Nigerian that Willie had ordained himself.

Notice that nowhere in my description of my reasons for rejecting the implicit offer does the color of my skin appear. I never felt I had to pretend to be Black, though I was always honored to be welcomed by that congregation as one of their own (as was my father, who preached at Good Shepherd on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of his ordination).

Which is, in my mind, the saddest thing about Rachel Dolezal: not that, pretending to be Black, she became a Black leader, but that she felt she had to pretend. I've read about her troubled childhood, her right-wing Evangelical home school upbringing, and all the speculation about how enticing it must have been to be welcomed into a minority community after being so badly treated as a member of the majority. Maybe she felt like she had no choice: to seriously pursue her interest in Black community organizing, she had to be a member of the community she wanted to lead.

My experience was different, but it was, after all, just my experience. Still: if a ginger-haired Swede like me could be embraced by this small corner of Portland's Black community, why not Rachel Dolezal?

Comments

Post a Comment